Stormy Forecast: Preparing Maine for Climate-fueled Winds and Flooding

We’re in one of the most active hurricane seasons ever recorded, with two months remaining. For only the second time, the 21 preselected names for storms ran out, leaving meteorologists to label the remainder using the Greek alphabet.

Tropical cyclones typically dissipate before reaching New England, so the impacts from past storms can slide out of “generational memory,” said MIT scientist Kerry Emanuel. Hurricane Teddy did not make the “rare, hard left turn toward Maine” initially forecast, but “I wouldn’t write off hurricanes at all” here, he cautioned, particularly as their dynamics shift in a warming world.

Hurricanes are acting differently

Hurricanes Laura and Sally underwent “rapid intensification,” jumping up category levels as they drew near shore. That sudden increase in wind speeds shortens the time to prepare or evacuate, and could be especially dangerous in Maine for residents of ferry-dependent islands.

This graphic depicts the pattern of Atlantic hurricane tracks in average October conditions, although every hurricane travels a somewhat different path – and climate change is making their movement harder to predict. Courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Hurricanes draw energy from warm waters, and temperatures in the Gulf of Maine have risen dramatically, but it’s “too small a body of water to have much effect,” Emanuel said, making rapid intensification less likely here.

But there’s another element of climate-charged storms that Maine likely won’t escape: more intense precipitation compressed into shorter time periods.

Like Hurricanes Harvey in 2017 and Florence in 2018, Hurricane Sally moved erratically and stalled, subjecting communities to prolonged precipitation, high winds and storm surge. This behavior is increasingly common, a 2019 study of Atlantic hurricanes confirmed, and can be devastating. In recent years, rainfall overtook storm surge as the leading cause of hurricane-related fatalities.

Fall is the season for hybrid storms

Late fall can bring an added risk of hybrid storms, like the Perfect Storm and Superstorm Sandy, that fuse tropical cyclones and extra-tropical cyclones (such as Nor’easters). “More powerful hurricanes in the tropics make more hybrid events more likely,” Emanuel said.

The total number of tropical cyclones within a hundred years helps illustrate that the peak season for Atlantic Basin storms is typically from mid-August to late October. Courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“October is known for having some very strong storms,” said John Cannon, senior meteorologist with NOAA’s National Weather Service. The polar jet stream can spawn Nor’easters that overlap with the peak of hurricane season.

Hybrid storms can intensify quickly in northern waters. The bomb cyclone that struck last October “was not on a weather map more than 48 hours before it arrived in Maine,” said Stephen Dickson of the Maine Geological Survey. If its peak had coincided with an astronomical high tide, which fortunately it did not, Dickson predicts the storm surge could have reached 3.9 feet, inundating 45 square miles along Maine’s coast and tidal rivers.

There’s a greater chance of hybrid storms “the more anomalously warm the water is,” particularly if other atmospheric conditions are at work – like “blocking patterns” in the North Atlantic, which scientists expect to become more frequent, said David Reidmiller, director of the Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s new climate center.

The storm surge from severe weather will be magnified as sea levels rise, Reidmiller added, creating impacts that will be “felt not just on the immediate coast but miles inland.”

Extreme vulnerabilities

Compared to the Gulf Coast states, Maine might seem relatively resilient to major storms – at least beyond its southern beaches and lowest-lying coastal and riverine areas. Much of the coast is famously rocky and a “huge tidal range has allowed us to dodge a lot of bullets,” said Susie Arnold, an Island Institute scientist.

Yet acute structural and social vulnerabilities put Maine at risk. Roadways, bridges, culverts, buildings and wastewater treatment systems can be flooded by storm surge and, increasingly, by rising seas. Populations that are poor, elderly or without reliable transportation are often at highest risk, being unable to easily relocate or even stock up to ride out a storm.

The Nature Conservancy’s online “coastal risk explorer” provides a “lifeline analysis” of these layered vulnerabilities, according to one of its creators, Eileen Johnson, environmental studies program manager at Bowdoin College. Municipalities can calculate – at a particular increment of sea-level rise – how many households would be cut off from emergency services and how much it might cost to address those transportation challenges.

While the open-source tool was designed to assess impacts from flooding that will occur “twice a day for eternity,” said Jeremy Bell, TNC’s climate adaptation program director, its sea-level rise increments can be a rough proxy for storm surge (without accounting for water velocity or wave action).

Numbers for a single town signal the magnitude of Maine’s collective vulnerability: among the 1,350 residents of Lubec, 227 addresses would be inaccessible if waters rose 3.3 feet. Upgrading that infrastructure would cost the community nearly $4 million.

Years of deferred maintenance have exacerbated structural vulnerabilities. The Maine Climate Council’s emergency management subgroup calculated a backlog of $325 million in projects already identified in county-level hazard mitigation plans, alongside “major state infrastructure at risk of changing climate conditions” (think Route 1 at Lincolnville Beach or the Deer Isle causeway).

Addressing ‘huge inequities’ in preparedness

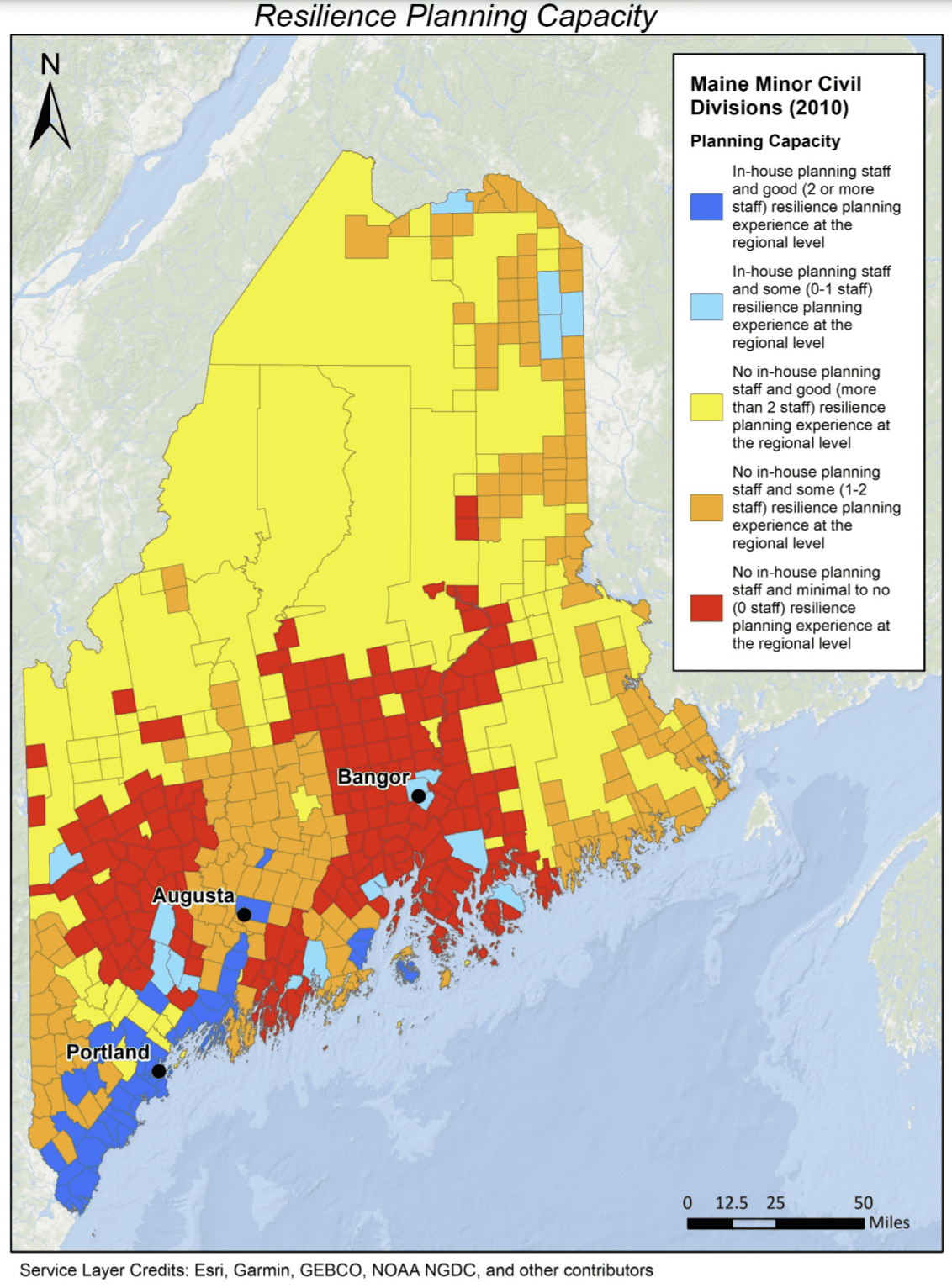

“A lot of towns that want the help and need the help,” said Bell, can’t get it. The Maine Climate Council confirms in its draft plan that “state government’s current capacity for assistance and financial support to towns is significantly undersized compared to the need,” citing that 72 percent of Maine’s communities have no local planner and insufficient or no regional support for resilience planning.

Nearly three-fourths of Maine communities lack a local planner and have insufficient or no regional support for resilience planning. Graphic courtesy of the Maine Climate Council.

What’s needed, Arnold said, is tailored community preparedness plans – in which local residents work with their county Emergency Management Agency and other specialists to identify hazards, assess resources and develop specific strategies for threats like flooding.

There are “huge inequities,” Bell found, in which even neighboring communities can have a “totally different ability to respond.” That reality must be confronted in the planning process, said Jill Trepanier, a climate scientist at Louisiana State University. She advocates paying extra attention “to help make sure rural communities and the disenfranchised are considered.”

While the climate plan does incorporate a preliminary equity analysis, the initial drafting of strategies “glossed over” scale issues – overlooking rural places already at a disadvantage, in the view of Tora Johnson, a social scientist at the University of Maine at Machias. “Smaller-scale communities have been losing out and some are way behind the curve.” Those in the Machias Bay region face some of the state’s highest social vulnerability and threats of land lost to storm surge. And, Emanuel said, “hurricane risk increases as you go downeast.”

To aid communities in storm preparedness, Tora Johnson believes, you need social scientists who are acutely aware of local constraints and capable of “spanning the distance between academia, technocrats and local decision-makers.”

“Whether communities will grapple with what they need to has more to do with psychology, sociology and economics,” she added, and with practitioners who understand local constraints and provide customized support.

Helping ‘resource-strapped’ communities prepare

Anne Fuchs, who co-chaired the Maine Climate Council’s emergency management subgroup and serves as state hazard mitigation officer at the Maine Emergency Management Agency, acknowledged that essential bind: “the best planning is always at the local level,” but those communities are “resource-strapped.”

Some towns have gotten state and federal grants and tailored support through a mix of college and university personnel, and agency and nonprofit staff. Knox County’s emergency management administrator, Ray Sisk, relied heavily on those partners in hazard mitigation planning and found – with the science they shared – we could “understand it, internalize it and act on it.”

But much of the state hasn’t received support and there aren’t enough people to provide it. Maine’s regional planning capacity has fallen markedly in the past decade, leaving entire counties with no support.

Trepanier suggests developing a program that would deploy recent college graduates or doctoral students to extend the capacity of Maine’s support network in helping communities prepare for storms.

To tackle the backlog of overdue infrastructure upgrades, the Council’s emergency management subgroup proposed a “state infrastructure climate adaptation fund,” a measure that 13 other states have taken to help communities meet the cost-share needed for federal grants, Fuchs said.

Asked how that fund would provide for the most vulnerable and least prepared communities, Fuchs indicated that those conversations “have not yet happened by design” because the Council will have no authority over such a fund. The Legislature would select an agency to manage the fund and consider those disparities.

“That’s a really important component of climate work,” Bell said, “to make sure we’re distributing resources equitably.”

Among many pressing needs for statewide climate action, addressing the inequities of storm preparedness must be a priority. With climate change accentuating existing vulnerabilities, too many Mainers are unprepared for the storms to come.

© Marina Schauffler, 2020. All Rights Reserved. Column reprints available upon request