‘Forever Chemicals’ on Farmland: A Slow-motion Disaster

Maine farmers are resourceful and resilient, but nothing could have prepared them for this invisible and insidious disaster. “We are… the human collateral of PFAS-contaminated biosolids,” observed organic farmer Nell Finnegan of Albion, casualties of a decades-long practice of spreading sludge tainted by “forever chemicals.”

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), thousands of unregulated chemicals widely used for stain and water resistance, end up in wastewater sludge. State and federal regulators have promoted these “biosolids” as economical fertilizers, unaware until recent years that pernicious chemicals were seeping into groundwater. While still under study, PFAS exposure is already linked to numerous health problems, including higher incidence of some cancers, reproductive issues and interference with immune and hormonal systems.

“They accumulate… little by little until we’re full of them,” Finnegan said. “Full of them like my family and I are.”

Sludge spread on neighboring lands contaminated their well — throwing their family into “a tailspin, a torturous limbo… teetering on the edge of losing everything. Our business, our home, our career, our future, our health. Everything.”

‘The safety net is being built in real time’

When PFAS contamination was found in 2016 on the Arundel dairy farm of Fred and Laura Stone, it was thought to be an anomalous tragedy. The state eventually ramped up testing of former sludge-spreading sites, and this winter numerous farms received news of PFAS contamination.

The Legislature had directed state agencies to “look into the problem without considering the ramifications of what would be done when contamination was found,” said Sarah Alexander, executive director of Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA). There no support structure in place for the farmers blindsided by this news.

In January, Maine state officials and nonprofit groups sprang into action.

“The safety net is being built in real time as the state and communities learn what is needed,” Alexander said. “It’s amazing that the state has been able to move as quickly as it has.”

Soon after farmers learned of the contamination, MOFGA invited Maine Farmland Trust (MFT) and state officials to a listening session with farmers, scheduled to last 1.5 hours, on how best to meet their immediate needs. It took them six hours, but the group developed a plan and forged the basis for a strong ongoing collaboration.

MFT and MOFGA established a relief fund to help cover costs of testing, income replacement and mental health counseling until more state funds could be allocated. The PFAS fund and consultations with MFT and MOFGA staff are available to all Maine farmers, not just to those affiliated with their groups.

“We want farmers to look at us as a resource and a partner,” said Amy Fisher, MFT’s president and CEO, “and we will try to be that for them.” MOFGA hopes to raise funds for a full-time case manager to help farmers navigate the process.

State agencies are coordinating efforts internally, with the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) conducting soil and water testing, the Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry working with affected farm owners and the Maine Centers for Disease Control and Prevention providing toxicology counseling and working to inform the medical community about PFAS-related health issues. University of Maine Cooperative Extension established a site for farmers and has trained its agricultural support network to field PFAS inquiries.

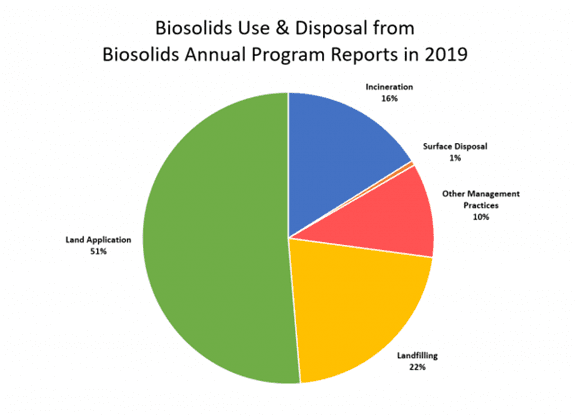

Maine is the first state to systematically test for the impacts of PFAS-tainted wastewater sludge (or biosolids), and it’s findings of widespread contamination don’t bode well for the nation’s farm communities and food systems. As of 2019, 51 percent of wastewater sludge nationwide was applied on agricultural lands, according to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data. Source: US EPA

The state should consider appointing a PFAS ombudsman who could be “a passport into the bureaucracy and someone to look out for farmers.” said Dr. Janis Petzel, a retired psychiatrist. The discovery of toxics undermines the most basic human needs for clean water, good health and the security of a safe home, she explained, making it harder for people to strategize effectively or clearly verbalize their thoughts. Having an ombudsman to listen carefully and carry their concerns to others could help.

‘A unique experience’

The trauma of toxic contamination is different than conventional natural disasters, which typically draw media attention and outpourings of public support, explained Sandy Wynn-Stelt, a clinical psychologist in Belmont, Mich., who has been advocating for PFAS action since high levels of the compounds were found five years ago in her neighborhood’s wells due to an abandoned industrial dump.

“There’s not the community rallying around you because nothing looks different, despite the ungodly amounts of this (PFAS) in our blood,” she reflected. “It’s a unique experience, which makes it more isolating.”

PFAS contamination can evoke the stages of grief, she found, particularly anger and depression. There is also a sense of being “duped,” alongside gnawing health anxieties and self-blame — however unwarranted. In her community, “it definitely was a mental health crisis and it was not recognized as such.”

Farmers can be especially vulnerable because they take justifiable pride in producing healthy food for their communities. Many already contend with stress due to the pandemic, the climate crisis, loss of dairy contracts, and the challenging economics of food production.

The trauma isn’t confined to those with contaminated water, Wynn-Stelt noted, acknowledging how hard this is for the state workers involved. Maine DEP Commissioner Melanie Loyzim has said that her staff members “feel like the Grim Reaper” delivering news of contamination.

Within weeks of getting the traumatic news, Maine farmers were already meeting and advocating for themselves. That pro-active response bodes well, Wynn-Stelt said. “The more you talk about it, the less anxious you get,” she observed. “Once you start taking some kind of action, that’s where the healing starts.”

‘We know enough now to turn off the tap’

Maine is the first state to comprehensively test for the impacts of forever chemicals from sludge spreading on farmland, a practice occurring nationwide where fully half of wastewater sludge is land-applied. Consequently, Maine has had to pioneer policy actions, moving to implement recommendations of a year-long PFAS task force.

The next policy step must be passage of LD 1911, which would ban land application of sludge and the land application or sale of compost derived from sludge. Two dozen companies and municipalities are licensed to convert sludge into compost, despite the state’s own finding that 89% of finished compost samples exceeded the screening level for PFOA, a common PFAS compound.

Adam Nordell, co-owner of Songbird Farm in Unity — another site of high PFAS contamination — summarized the importance of LD 1911 this way: “No one can undo the historic contamination of our land. But we know enough now to turn off the tap.”

A second bill before the Legislature, LD 1639, would prevent the state-owned Juniper Ridge landfill, managed by Casella Waste Systems, from accepting construction and demolition debris that originated out of state and is laden with PFAS and other toxics, increasing the contaminated leachate entering the Penobscot River.

Staff members of Maine’s congressional delegation recently participated in a listening session with farmers and are drafting a joint letter to federal agencies requesting more action.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is belatedly moving to regulate a handful of PFAS compounds, out of an estimated 9,000, and revise its outdated PFAS health advisory. But its website still promotes the “economic and waste management benefits” of spreading toxic sludge on agricultural lands, oblivious to the long-term costs.

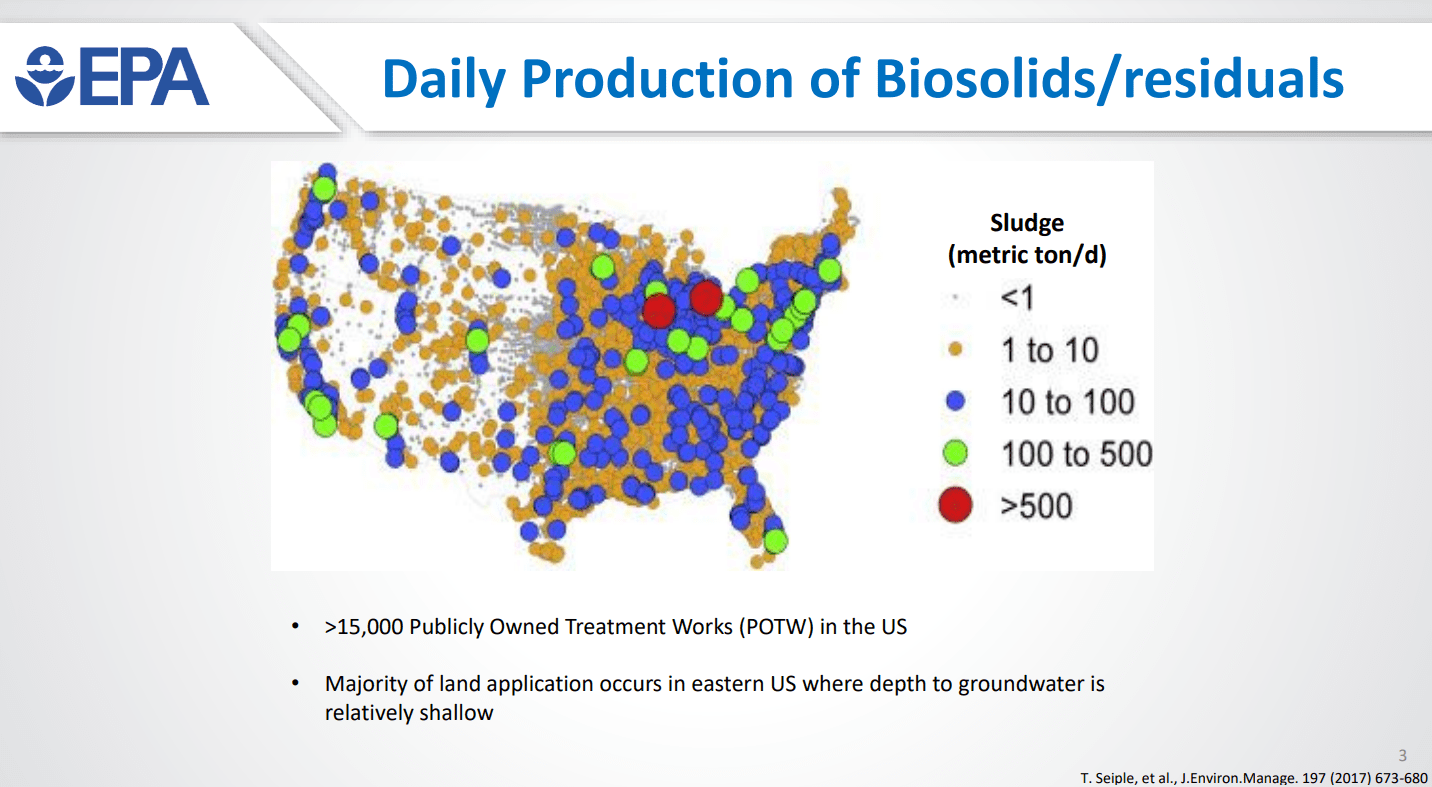

The spreading of wastewater sludge (biosolids) on agricultural land, a common practice dating to the 1980s, is concentrated in the eastern U.S. where groundwater depth is relatively shallow, raising concerns about widespread PFAS contamination affecting drinking water. Source: EPA webinar, “PFAS in Biosolids,” Sept. 23, 2020.

The DEP estimates $20 million will be needed annually to complete PFAS testing (slated to run through 2026). LD 2013, a newly drafted bill being heard March 15 by the Legislature’s Joint Standing Committee on Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, proposes a $100-million fund to start addressing long-term costs such as health monitoring, land buyouts and research into soil and water remediation methods.

Another ‘long developing environmental disaster’

Dr. Lani Graham, a retired physician and former director of Maine’s Bureau of Public Health, likens PFAS to lead contamination, being another “long developing environmental disaster” with echoes of the tobacco and opioid public health crises.

PFAS manufacturers, such as DuPont and 3M, followed a similar corporate playbook. Despite internal research from the 1960s onward revealing the toxicity and longevity of PFAS compounds, the corporations continued production, knowingly exposing workers and contaminating water supplies. Through tenacious legal work spanning two decades, attorney Robert Bilott brought to light this sordid history, captured in the film “Dark Waters” and his memoir “Exposure.”

While some PFAS class action lawsuits have succeeded (and one by Maine residents exposed through paper mill sludge is in process), clean water activist Erin Brockovich counsels communities not to pin hopes on distant legal settlements or federal support. Local people must get creative, she observes, and work together to devise the best solutions they can.

Maine is off to a good start, with researchers studying plant uptakes of PFAS, legislators acting decisively and the state working to ensure the safety of Maine’s food supply. There is already talk of converting some contaminated sites into solar farms.

Being at the leading edge of a devastating public health crisis is exhausting, even for the Dirigo state. More support is needed for everyone involved, from traumatized farm families to overloaded state and nonprofit workers. Following a protracted pandemic, the PFAS crisis can feel crushing.

The constructive early response offers some reassurance that Mainers will rise to this challenge. We are, after all, resourceful and resilient.

© Marina Schauffler, 2022. All Rights Reserved. Column reprints available upon request