Navigating toward Cleaner Transportation

With global carbon pollution at an all-time high and transportation the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Maine and the U.S., it’s encouraging to see the auto industry pivoting to electric vehicles (EVs) and more people acquiring them.

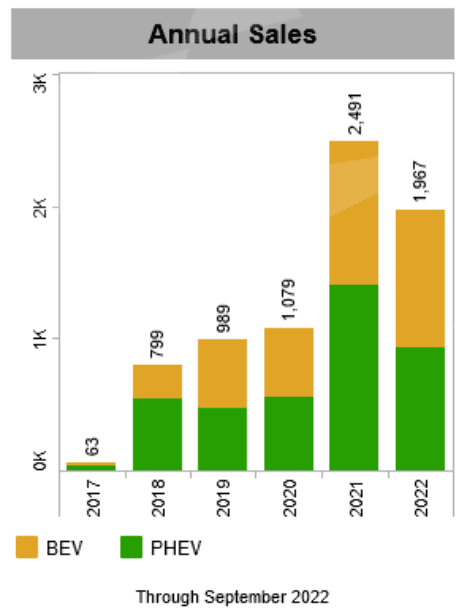

Maine is installing new EV chargers, a critical step in convincing more people to relinquish gas-powered vehicles. A study released last month of “EV-friendly” states ranked Maine eighth, with 1,602 residents per charger in 2022, helping to power more than 3,000 all-electric vehicles.

But achieving emissions-free transportation requires reinventing how we get around, not just what we drive.

The paradigm shift of battery power

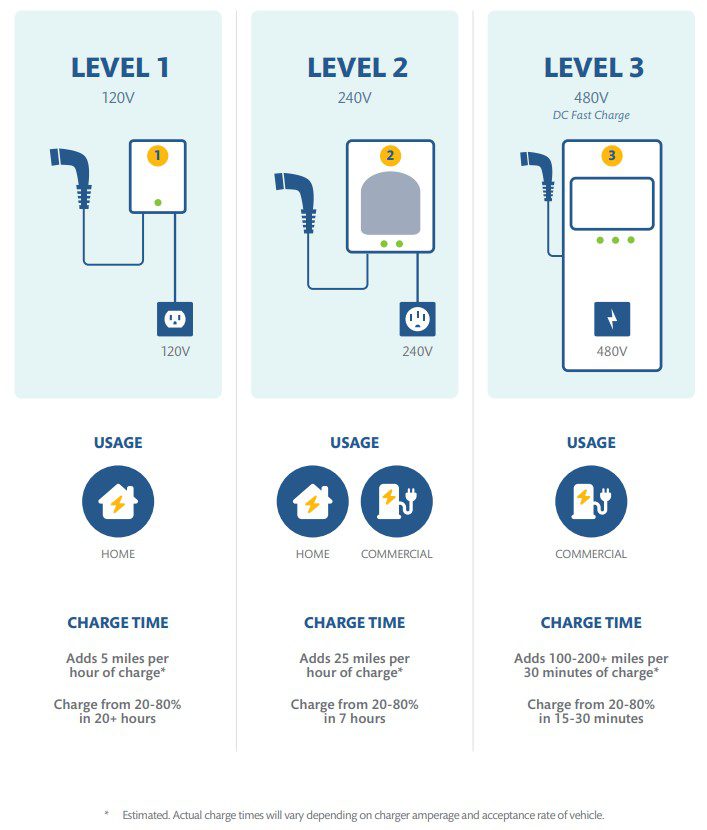

For drivers accustomed to gas-station refueling, it’s an adjustment to use the current mix of charging stations, both networked (managed by large companies) and non-networked (such as those installed by municipalities or local businesses). A guide to home and on-the-road charging for EV owners from Efficiency Maine Trust helps illuminate this less-than-intuitive system.

Maine has roughly 400 charging stations currently, most of them Level 2 chargers, but state and federal funds are now committed to installation of many more Level 3 (DC Fast) charters. Credit: Efficiency Maine Trust.

Some networks require a customized app to pay, and not every charging station operator maintains equipment consistently. This should improve over time, according to Molly Siegel, Efficiency Maine’s program manager for electric vehicle initiatives: All DC fast-charging stations funded by the state or the federal Infrastructure Act must be operational 97 percent of the time, offer multiple payment options and not require network membership for use.

State-funded DC fast chargers installed to date are in the ChargePoint network, according to Siegel, which offers — on request — a free RFID (radio-frequency identification) card to facilitate payment without a membership requirement.

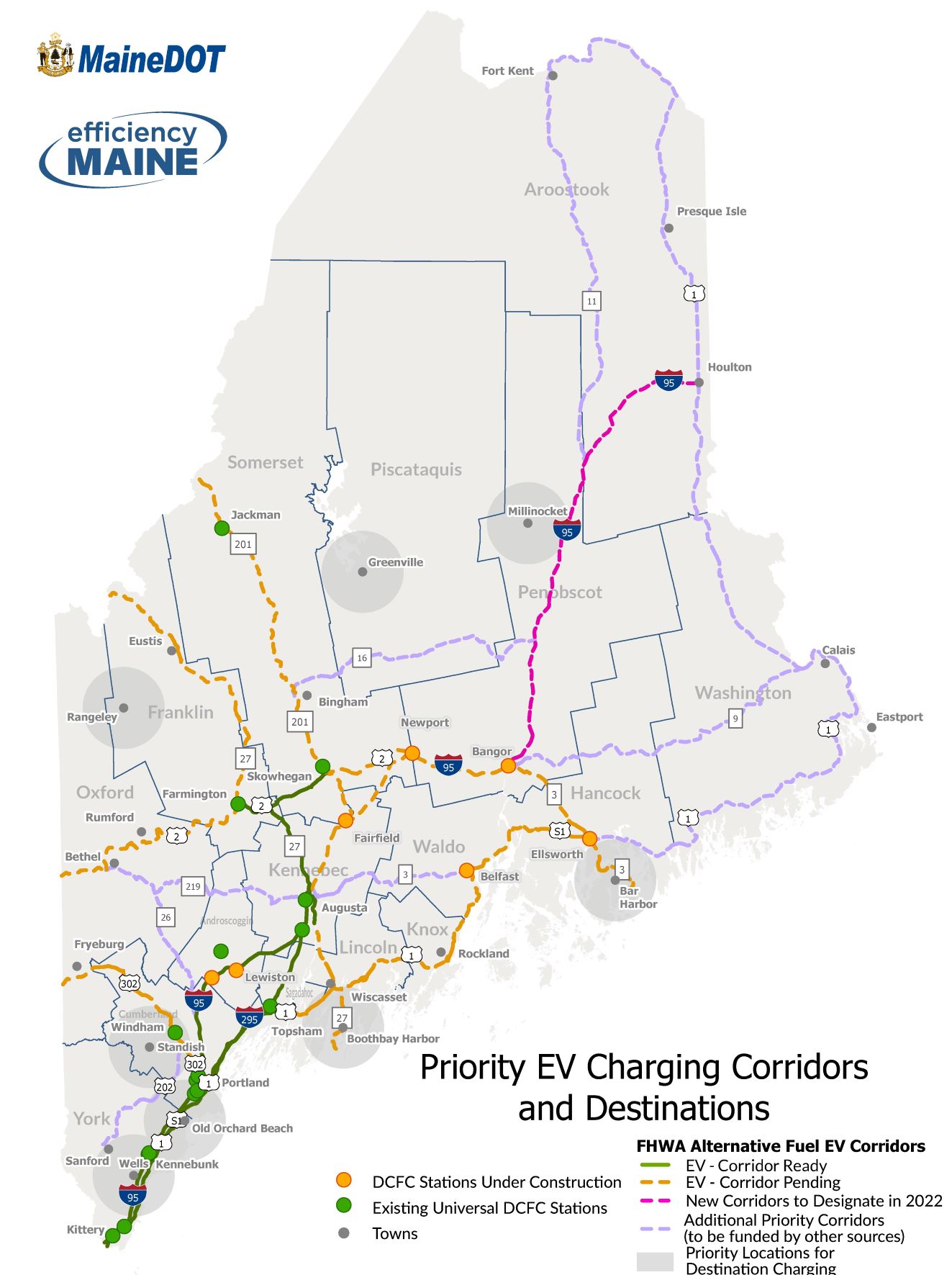

Last fall, the U.S. Department of Transportation approved Maine’s plan for improved EV charging infrastructure, which will significantly increase charging stations in rural areas where, given low traffic levels, “the private market is unlikely to step in,” Siegel said.

Efficiency Maine has installed Level 2 chargers at 56 locations and DC fast chargers at eight, with six more under construction; the federal funding is expected to add roughly 55 DC fast-charging locations and more than 250 Level 2 locations, which Siegel noted will allow drivers within four years to “travel north to south and east to west across our state without experiencing ‘range anxiety.’”

Selecting the range you really need

The road to clean transportation will require shifting from the SUVs and pickups that currently constitute 80 percent of new vehicle purchases in the U.S. Electrification doesn’t change the fact that bigger, heavier vehicles are less efficient; a Nissan Leaf or Tesla Model 3, for example, will travel roughly twice as many miles per kilowatt hour as a Ford Lightning truck.

Maine submitted a plan identifying priority locations for new fast chargers that will be funded under the federal Infrastructure Act. Source: Maine Plan for Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Deployment (2022).

Automakers that have super-sized their vehicle models over recent decades now market larger EVs with hefty batteries. But heavy battery packs are costly in financial and ecological terms, and their added weight poses a potential safety hazard for other vehicles and pedestrians.

In selecting an appropriate EV, buyers should focus on the battery range required for their driving needs. A few examples from EV drivers I know may demonstrate the value of advance planning.

One person who mainly drives close to home bought a used EV with a range of 66 miles, and has put 45,000 miles on a car that cost under $8,000 when nearly new. Another couple that drives frequently between two properties chose a vehicle with enough range that they could recharge at either location without stopping on the road.

A third person with a long work commute sought to drive that round trip without charging the battery over 80 percent or running it below 20 percent (a common recommendation to extend battery life). Factoring in efficiency lost to cold weather and highway speeds, he looked for a vehicle with a range at least 2.5 times his daily commute.

Maine residents drive 30 to 33 miles a day, on average, according to a 2017 survey, so few of us may actually need what’s now the median battery range of 247 miles for new vehicles (according to data scientist Hannah Ritchie). “Most people’s range anxiety isn’t about day-to-day driving,” Ritchie wrote. “It’s about those rare long trips for a holiday or special occasion.”

A study published in the journal Energies confirmed this point. After reviewing data from more than 300 drivers of gas-powered vehicles to assess which sorts of EVs could meet their needs, researchers found that nearly 40 percent could get by 100 percent of the time with an all-electric car like the base model Nissan Leaf (which has a 150-mile range and a 40-kWh battery).

Our family owns that base model Leaf and it meets our needs exceptionally well — about 95 percent of the time. An EV with a larger battery would cover that remaining 5 percent when traveling longer distances with time constraints, but at a significant financial and environmental cost.

Establishing a network of car-sharing programs

Scott Vlaun, director of the Center for an Ecology-based Economy (CEBE) in Norway and an EV driver for nine years, told me he also faces that issue occasionally with his own vehicle. And he has a solution in mind: a local car-sharing program with a handful of electric vehicles available for rent hourly or daily, all parked under a solar canopy that generates much of the power to charge them. He’d like to see that vision manifest across Maine.

Annual EV sales of all-electric (BEV) and plug-in hybrid (PHEV) vehicles increased markedly in the five year period between September 2017 and September 2022. Credit: Alliance for Automotive Innovation.

Car sharing could help address the inherent inequities of auto-centric transportation, which drains up to 27 percent of the income from households with the lowest earnings. It can meet the needs of young adults who can’t afford or simply don’t want their own vehicles, retired drivers looking to save expenses on a fixed income, single-car families who occasionally need a second vehicle, and drivers of low-range EVs who need an occasional ‘trip’ car.

For-profit car-sharing has a bit of a “boom and bust reputation,” said Quinn Salinder, operations manager for CarShare Vermont, a nonprofit that has been running for 16 years around Burlington. But the non-profit model works well in numerous places, he noted. Expenses are primarily covered by membership and usage revenues, with special rates for low-income members.

Efficiency Maine could help establish that sort of car-sharing model here, Vlaun said, adding that its new Green Bank could potentially help fund it. Setting up such programs is not simple, he added, but “it can be done. It has to be done.”

Vlaun would also like to see a fleet of electrified small-passenger vans, with bike racks, running circuits between towns, and more work to make areas around downtown centers safer for biking. Active (human-powered) transportation will be critical in drawing down transportation emissions quickly, studies have shown.

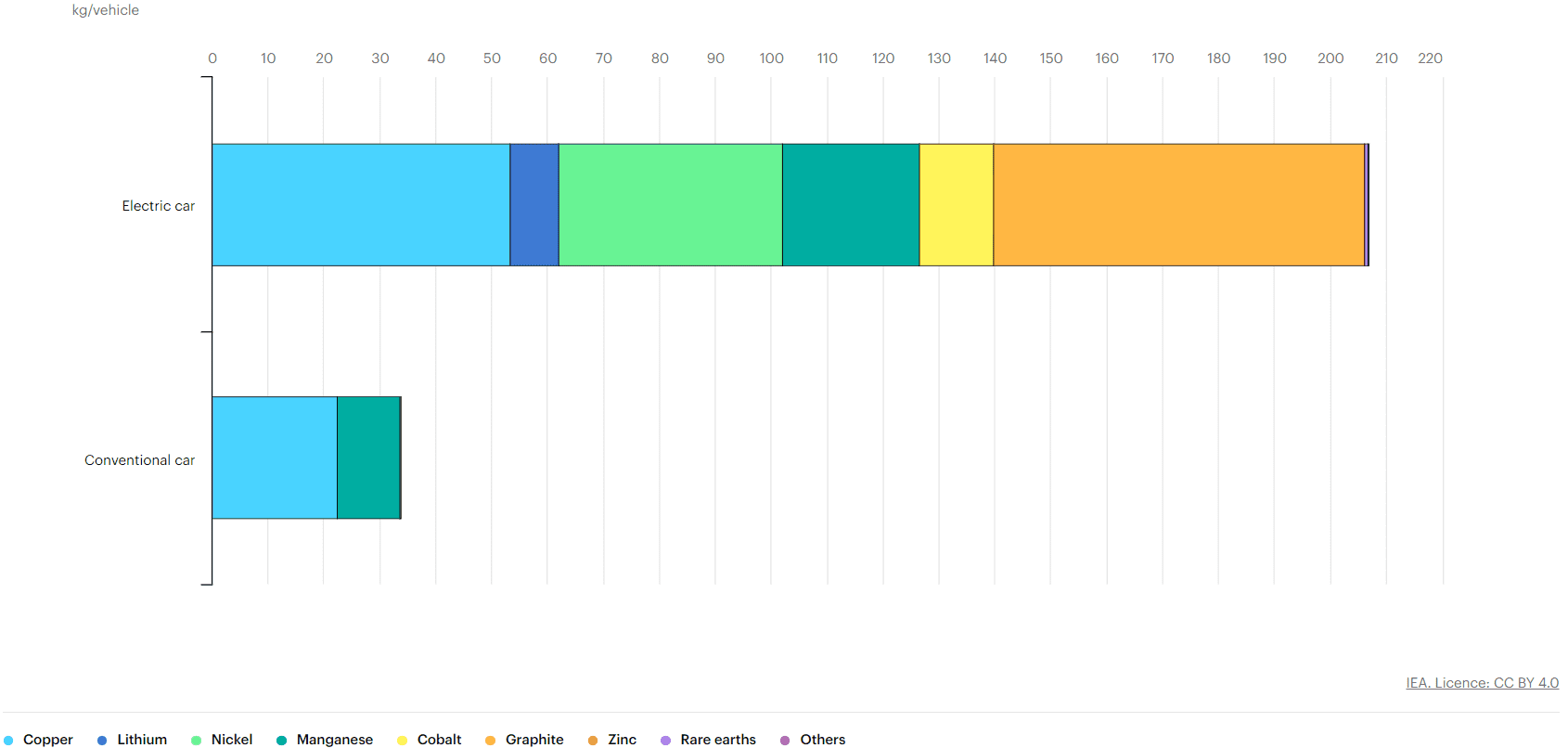

Decreasing mining impacts

Reducing car dependence and encouraging smaller EVs (as Europe has done) provide benefits that go well beyond lower greenhouse gas emissions. EVs require about six times more minerals than fossil-fuel-powered vehicles, and mining is notorious for devastating human rights violations, and for damaging water and air quality, ecosystem health and biological diversity.

Minerals used in electric cars compared to conventional cars. Credit: International Energy Agency.

As Maine weighs potential lithium mining in Newry, it’s worth noting the findings of a recent report, Achieving Zero Emissions with More Mobility and Less Mining (summarized by co-author Thea Riofrancos on journalist David Roberts’ podcast, Volts): If the U.S. simply switches out gas-powered vehicles for EVs, it will need three times the current global production of lithium by 2050. But with smaller EV batteries, more public transit and reduced dependence on cars, researchers estimated that lithium demand could drop by up to 92 percent.

Maine could follow the example of Norway, which leads in EV adoption, and impose a weight-based vehicle tax on gas-powered and electric vehicles. Those fees could help account for the higher impact of heavier vehicles — in embodied mineral and metal resources, faster tire wear (which generates microplastics pollution) and safety threats, while helping compensate for declining revenues from gas taxes.

Efficiency Maine has leverage to help reduce demand for lithium and other minerals, Vlaun noted, by restructuring its EV incentives to provide the greatest rebates on smaller-battery vehicles. That could further lower the cost of the most affordable EVs, potentially making them more accessible to low-income households than the Trust’s present tiered incentives for low- and moderate-income households.

The current rebates exclude the most expensive EVs, but still provide the same incentive for a Rivian R1T truck (with a $73,000 price tag and a 135-kWh battery) as for smaller cars with batteries less than half that size).

Scaling state incentives to encourage purchase of the most resource- and energy-efficient vehicles “could definitely affect the market in a small way and what dealers focus on,” Vlaun said. States need to “put pressure on manufacturers not to abandon the lower-range cars.”

© Marina Schauffler, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Column reprints available upon request