A Tangle of Plastic Pollution Ties Back to Our Clothes

The soft clouds of gray lint that slide off clothes dryer screens are tangible evidence of the dryer’s tumbling abrasion. Each handful comes at a cost, shortening the lifespan of garments. But the true cost of this innocuous-looking fuzz is far higher.

Seventy-five percent of global textiles are synthetic (derived from petroleum rather than plant-based materials like cotton or hemp). So lint typically contains countless enduring plastic fibers. A single fleece jacket can shed up to 250,000 microscopic plastic fibers (microfibers) over its lifetime, researchers estimate.

Not all lint is captured by the dryer’s internal screen, as anyone who has examined an external clothes dryer vent can attest. Microfibers spew out of dryer vents into the surrounding environment, an interesting backyard study conducted by two scientists found, adding to the large and growing problem of microplastic pollution.

‘What we found was unexpected’

One of those scientists, Rachael Miller, runs Rozalia Project, a nonprofit focused on innovative action to reduce marine pollution. When project staff first learned of microfibers in 2013, “it was one of those problems that just screamed at us,” she recalled.

Researchers in the U.K. had traced plastic microfibers in rivers and oceans back to clothes washers, which — like dryers — abrade clothes and send a plume of microfibers into wastewater.

As Rozalia Project began testing waters for microfibers, researchers realized just how ubiquitous these runaway fibers are. It proved challenging to avoid contaminating water samples with fibers from their own clothing, even when samples were exposed to air for less than a minute. We are all Pigpen,” Miller observed, “but instead of walking around in a cloud of dirt we’re walking around in a cloud of fiber.”

That realization was sobering for Miller, personally as well as professionally. Being an outdoor sports enthusiast who routinely wears synthetics to stay warm and dry, she said “I live and literally breathe this stuff.”

There’s a legitimate need for some quick-drying materials for outdoor wear, but much of the “fast fashion” synthetics now manufactured carry a high environmental cost, both in microfiber pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Whereas previous generations washed and air-dried durable materials with biodegradable fibers, many consumers now choose short-lived, cheaply made synthetics with fibers that shed readily and last for centuries.

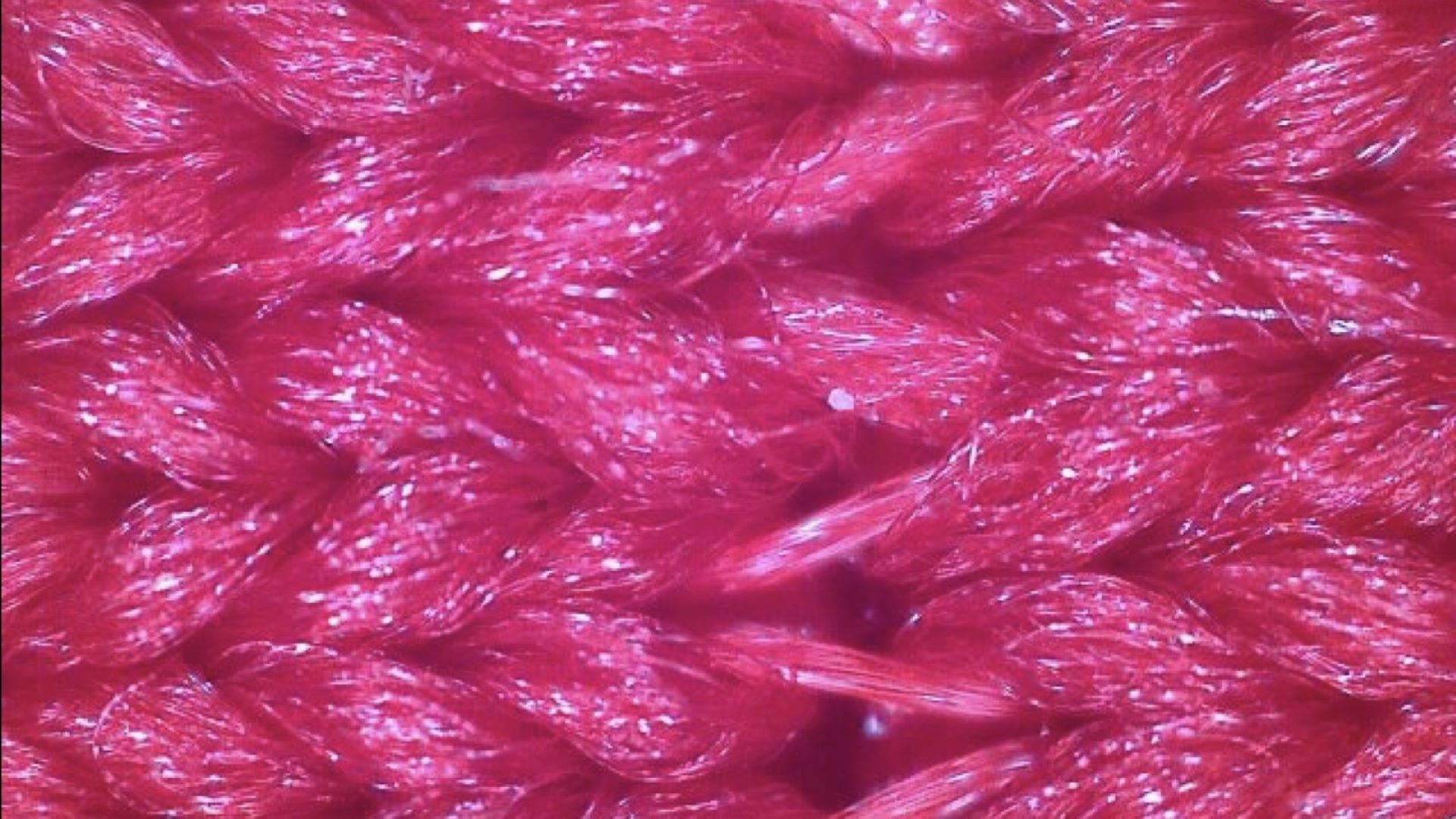

A microscopic view of a synthetic top illustrates how vulnerable fibers are to breakage. Photo courtesy of Rozalia Project.

Rozalia Project undertook water-sampling along the 300-mile length of the Hudson River in 2016, testing for microfibers at three-mile intervals. The project’s sailing research vessel, American Promise, normally travels the coast of Maine in summer, but now the staff wanted to know, in Miller’s words, “what does microfiber pollution look like in the wild?”

Miller hypothesized that the vessel’s crew would find the highest concentrations of microfibers directly below wastewater treatment plant outfalls, but “what we found was unexpected.” One hot spot was near such a source, but two were far upstream in relatively rural settings. Clothes washers were clearly part of the problem, but the river study expanded “what we had to start thinking about in terms of important potential sources,” Miller said.

‘The tried and tested blanket method’

Kirsten Kapp, a scientific colleague of Miller’s in the Pacific Northwest, did similar water-testing along the Snake and lower Columbia rivers and found the highest microplastic concentrations near agricultural areas, presumably due to spreading of wastewater treatment sludge laden with microfibers.

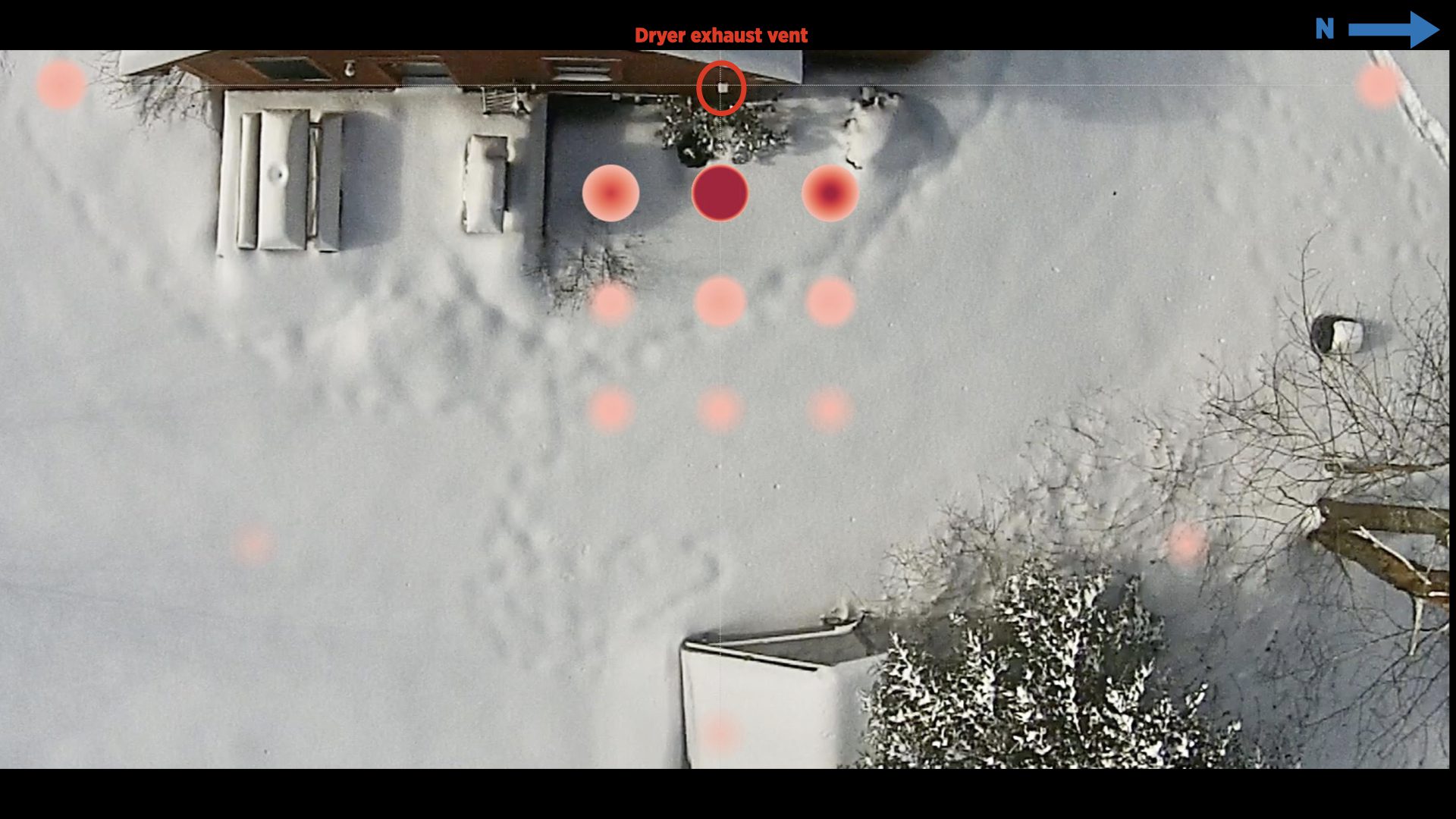

Looking for other sources of microfibers, the two scientists decided to assess dispersion of fibers from their home clothes dryer vents, a project that coincided with pandemic lockdowns when little other research could be done. Using what Miller called “the tried and tested blanket method” other scientists had used with clothes washers, they soaked and dried new pink fleece blankets — measuring the spread of magenta lint that accumulated on snow cover outside each of their homes.

In both cases, the microfibers spread out for yards. Had the plastic fibers not been collected for research, they would have washed off in snowmelt and wound up in the nearest river or settled into soils.

An aerial view of one backyard dryer study site shows how pink microfibers from a test blanket concentrated around the dryer vent but spread out across the snow outside the home. Photo courtesy of Rozalia Project.

Both blankets generated most microfibers from dryings early in their life, a pattern other researchers had found with blanket washing. That finding points to the need for changes in textile production, Miller noted.

Before textiles are even manufactured into garments, they should be prewashed and pre-dried with appliances that can capture those fibers. This change in the textile industry could greatly minimize the initial release of microfibers from clothing into the environment.

‘The solutions are going to come from things that are just being thought of now’

With synthetic textile production forecast to triple by 2050, there’s a clear need to rethink the constituent elements of what we wear. On climate grounds alone, it won’t be sustainable to vastly expand the production of textiles using fossil fuels. And there’s growing evidence that microfiber pollution threatens wildlife and human health.

Innovation in materials engineering could create new fabrics using renewable resources (particularly ones that are byproducts of other processes): “The solutions are going to come from things that are just being thought of now,” Miller said; what we need “is to achieve Gore-tex like performance from entirely naturally derived materials.”

Fortunately, some of that research is already underway, supported by efforts like the nonprofit tech company Conservation X Lab’s Microfiber Innovation Challenge.

Until all microfibers are fully biodegradable, filters on new clothes washers and dryers or appliance redesigns could limit further pollution. Legislative measures to require these changes have already been adopted in France and are under consideration in California, New York and Connecticut, as well as the U.K. California’s new statewide microplastics strategy recommends that the textile industry develop fiber fragmentation/shedding standards and associated product labeling, invest in natural textile processing, evaluate potential toxicity of additives used, and “propose a policy framework to reduce synthetic fiber production and waste.”

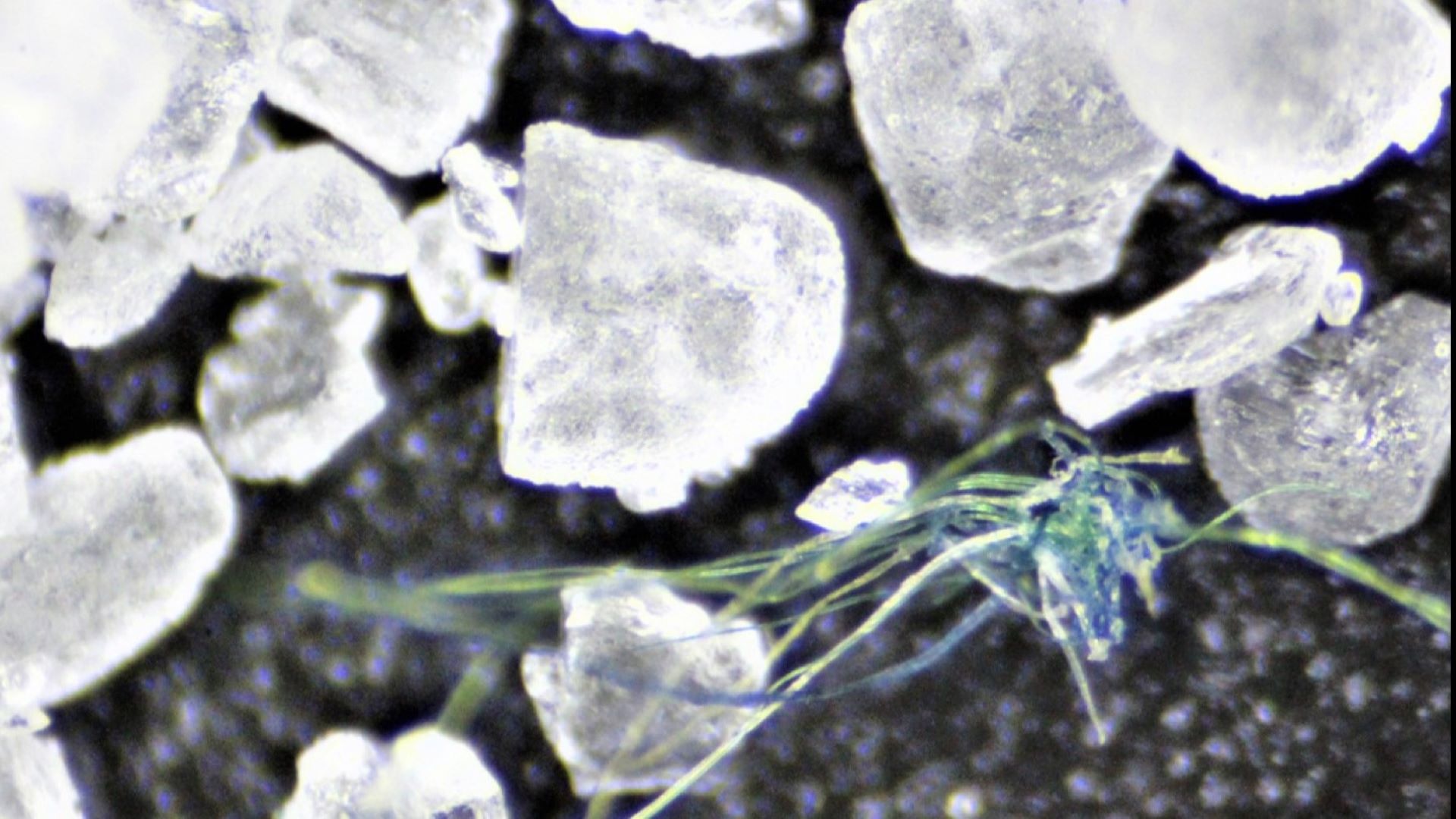

The tiny size of microscopic plastic fibers belies a problem of vast proportions. Plastic threads under a microscope appear here in relation to salt crystals. Photo courtesy of Rozalia Project.

A federal Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act, reintroduced in March 2021, includes provisions to require filters on new clothes washers and to study ways to better prevent microfiber pollution over the life cycle use of textiles. Among Maine’s delegation, only U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree is among the 127 co-sponsors.

In Rozalia Project’s work to combat plastic pollution, Miller has found that “lots of littles make a big.” That principle applies to consumer actions (see sidebar) and to states (which can hasten change among appliance and textile manufacturers through legislation).

The solutions are in sight, but in Miller’s view “the problem is the speed at which these things move.” Consumers need to apply more pressure to clothing companies, appliance manufacturers and elected officials “The science is moving fast” in terms of learning about microfiber sources and pathways, she reflected, but in the halls of government and industry, “they’re moving at the speed of corporateness.”