The urgent need to get off fossil fuels is indeed stretching our imaginative capacity, particularly in Maine — a state renowned for its old housing stock and high dependence on home heating oil. Houses that once seemed like more or less leaky boxes are in fact dynamic energy systems.

Energy coaches could help navigate the housing transition

Homeowners hoping to upgrade those systems to operate with greater efficiency and less carbon pollution can easily get bogged down in research, searching for energy-savvy contractors, and sorting out incentives and financing.

An Energy Coach pilot program, newly launched by the community nonprofit York Ready for Climate Action (YRCA), offers homeowners support from a third-party advisor, someone with no financial stake in the choices they make. The volunteer coaches undergo more than a dozen hours of training, but they don’t serve as technical experts, said Rozanna Patane, a YRCA board member spearheading the new program.

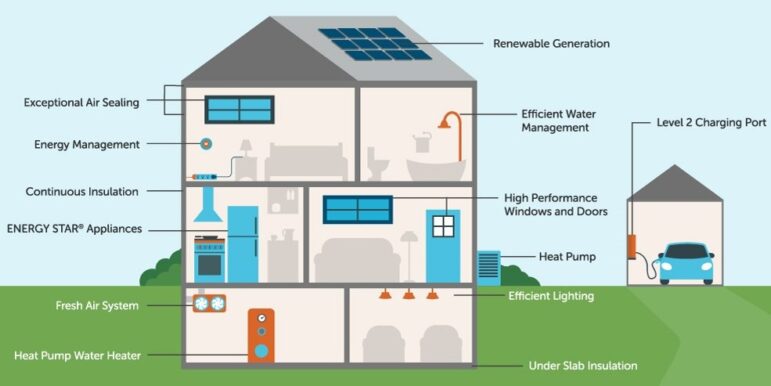

Coaches help homeowners look at a breadth of options—from weatherization and heat pumps to solar power and electric vehicles. They offer assistance locating skilled contractors, identifying relevant rebates and loan programs, and finding answers to technical questions.

The coaching offer came just in time for the first homeowner to participate in the program. Having recently bought an older house, she was unhappy with energy upgrades that had been done and uncertain how to proceed. Talking through options at length with a YRCA coach gave her renewed motivation and focus. The coach followed up with a two-page summary, and promised to check back in a month. “It’s amazing to have someone offer to do such intense work,” the homeowner said.

Home energy upgrades can be especially hard for lower-income households, where significant renovations may be needed before weatherization can be completed or heat pumps installed. To address this disparity in York, YRCA has committed to fundraising for a Household Equity Fund, which will offer grants to qualified families — helping close the gap between state programs and household resources.

Scaling up support for homeowners

York has already inspired several Maine communities to consider similar programs, and its two-year pilot may help determine “how to make [this model] work in volume,” Patane said. But many of Maine’s nearly 500 municipalities don’t have the capacity to implement a similar program. How might their residents get coaching support?

The Hawai’i State Energy Office runs a Clean Energy Wayfinder Program that trains eight individuals to serve for a year providing this sort of individual and community-scale coaching, particularly in low- and moderate-income communities. There’s “definitely interest and conversations” around launching something similar in Maine, said Kirsten Brewer, Maine Climate Corps Coordinator with Volunteer Maine, but it would depend “on funding coming in and sponsors willing to run these programs,” each of which is required by Volunteer Maine to have a program director to oversee corps members.

Maine does have a few similar positions now, including an Island Institute fellowship and one of two new “Maine Service Fellow” positions, which will support the Passamaquoddy Tribe in energy efficiency work. Markedly more coaches are needed to support homeowners statewide.

Clean energy is a priority area for the federal AmeriCorps program, Brewer said, but the local capacity to administer those federal grants can be a limitation. While Greater Portland Council of Governments has established an AmeriCorps-funded Resilience Corps, few regional agencies in Maine have sufficient capacity to oversee corps members’ work.

The need for lower-interest energy improvement loans

Another big hurdle for many households is getting the up-front capital needed to upgrade to an efficient and electrified home. “With fossil fuels, you save now and pay later; with renewables, you pay now and save later (including the planet),” engineer and inventor Saul Griffith wrote in his 2021 book “Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for Our Clean Energy Future.” The obvious solution, he argued, is to offer “climate loans” at low rates (like 3 to 4 percent) that enable people to start saving money from renewable power right away.

Efficiency Maine Trust has long provided incentives to help Mainers acquire more energy-efficient appliances, light bulbs, heating systems and, most recently, electric vehicles. The Trust offers some loan opportunities and grants for low-income households, said Michael Stoddard, its executive director, but “we’ve been sort of capital-constrained.”

Federal funding through the Inflation Reduction Act could “significantly increase the capital available,” Stoddard added, making it possible for Maine to move closer to Griffith’s vision. The hope is to offer loans that are, in Stoddard’s words, “cash-flow positive from day one; the amount you’re saving on energy is higher than your loan obligations.”

Efficiency Maine is currently holding discussions with community banks and credit unions around the state, Stoddard said, working to develop a guaranteed loan fund that could extend borrowing levels for low- and moderate-income families and offer subsidized interest rates even to those with higher credit scores. It’s a model successfully pioneered by the Connecticut Green Bank, where people can borrow up to $40,000 for a wide range of energy upgrades, including building performance, heating/cooling and renewable power.

Joining greater funding with expanded coaching

If the York pilot program confirms the value of community-scale energy coaching in helping homes rapidly reduce fossil fuel reliance, Maine should launch and oversee a statewide effort, potentially involving paid coaches serving as part of Maine Climate Corps.

Efficiency Maine would be a logical candidate to oversee that initiative since it already serves as the state’s central hub for energy resources, training and technical support. Stoddard isn’t ruling out the possibility that Efficiency Maine could lend more support to a statewide energy coaching initiative in the future. “If we saw there was a gaping hole in awareness and consumer demand,” he said, “we would stand ready to step into that.”