Can’t Save the Forest for the Trees

In forests, we expect slow change. Trees gain height and breadth by small degrees, and the mix of species shifts gradually over decades. But reality no longer conforms to our expectations. Many tree species in Maine and elsewhere are rapidly succumbing to non-native pests.

This transformation is evident along one of my favorite trails, which follows a brook through a mix of woodland ecosystems. The trail begins in a floodplain dominated by brown ash and dotted with winterberry shrubs. Farther upstream, it winds into a hemlock stand that shields the brook from sun. Then the trail climbs a hillside of beech trees, dense with leaves that glow green in spring and gold in fall, before mellowing to a pale copper in winter.

For years, every opportunity I have had to walk in the presence of these trees has buoyed my spirits. Now it brings a lump to my throat.

My heart cannot bear what my head knows; in this region, these three tree species are doomed. Most of them will likely be dead within a decade or so due to the arrival of invasive threats: emerald ash borer, hemlock woolly adelgid and beech leaf disease.

A devastatingly rapid decline

For regional populations of American and European beech, time is fast running out.

Beech leaf disease was first found in Maine just 14 months ago, when landowners in Lincolnville noticed dark banding on the ridged leaves of their trees. Some leaves had already curled and grown leathery.

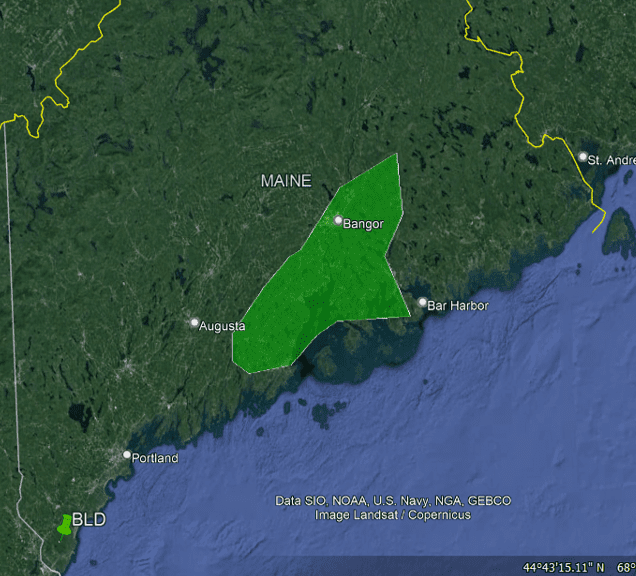

By bud-out this year, their beech stand had lost much of its canopy, remaining in a perpetual winter of bare branches and gray trunks. This scene is repeating itself across Maine, where beech leaf disease has spread through the Midcoast and Penobscot County and has recently surfaced in York County.

The Lincolnville woodland where beech leaf disease was first discovered in May 2021 (on left) shows how much canopy loss can occur in a single year, with the image on right taken in May 2022. Photo by Aaron Bergdahl of the Maine Forest Service.

The damage appears to come from a nematode, a microscopic worm-like creature that multiplies in the buds and impairs the gas exchange vital to photosynthesis. It wreaks “mechanical havoc” inside the leaf structure, according to Cameron McIntire, a plant pathologist at the USDA Forest Service in Durham, New Hampshire.

Scientists are still struggling to resolve many unanswered questions, such as how these nematodes are transported, and whether they work alone or in concert with bacteria and fungi.

The nematode, a sub-species of one native to Japan, was first discovered in Ohio a decade ago. Hemlock woolly adelgid and emerald ash borer, both Asian natives as well, were found in this country in the early 1950s and in 2002 respectively, spreading slowly since then and reaching Maine in 2003 and 2018. “In areas where these pests and diseases are already established, we can expect to observe significant dieback of our native tree species unless active measures are taken to slow the spread,” McIntire noted.

At present, beech leaf disease is concentrated in the Midcoast and Penobscot County, but it has recently appeared in York County as well. Photo courtesy of Maine Forest Service.

Within their native ecosystems in Asia, these species have natural predators and are among trees that have evolved to thwart their attacks. But North American trees have no such defenses.

For the beech, the nematode’s arrival follows a long-standing struggle with beech bark disease, a one-two inflicted by the beech bark scale, an insect introduced from Europe more than a century ago, and a fungal pathogen. The bark disease has gradually killed off most of the grand beeches with silvery smooth trunks too large to encircle — leaving smaller beeches with pocked and pitted trunks. Weakened by beech bark disease, the trees are especially susceptible to this latest attack — and most will likely die within three to seven years.

Through the eyes of wildlife

In the years of walking the brookside trail, I’ve come to appreciate the diversity of life reliant on these trees: migratory warblers, downy and pileated woodpeckers, chickadees, nuthatches, turkeys, deer and coyotes. One hemlock is a particular favorite among deer as its outer branches drop with the weight of snow to create a sheltered spot for them to bed down out of the elements.

My appreciation for these woodlands mushroomed — so to speak — when I learned of the remarkable community of mycorrhizal fungi underfoot that may aid the transfer of nutrients that happens among trees. What Canadian forest ecologist Suzanne Simard calls the “wood wide web” represents a cooperative exchange we are only beginning to understand.

In early stages of beech leaf disease, a dark banding is evident on the leaves. Leaves subsequently often shows signs of curling and may become leathery. Photo by Aaron Bergdahl of Maine Forest Service.

So far, few beech trees — young or old — appear able to resist this parasitic nematode. But I keep hoping that pines, oaks, maples, birches and other unaffected trees can somehow assist the afflicted beech, help hemlock resist the tiny aphid-like insects sucking nutrients from its twigs, and aid ash in fighting off bark-boring beetles.

Ash holds a sacred place in the cosmology and culture of the Wabanaki, and beech is what biologists call a “keystone species,” nourishing many members of the forest ecosystem through its, sap, catkins, leaves, nesting sites and valued nuts. Second only to butternuts in protein, beech nuts help sustain birds, squirrels and even brown bears.

Beech provides food for caterpillars of 126 species of moths and butterflies, according to entomologist Douglas Tallamy, author of “Bringing Nature Home.” With ash trees, that number rises to 150 species.

‘Manage for diversity’

Tied into global trade and sometimes fueled by the changing climate, the spread of non-native pests is a wicked problem.

With luck, individual trees may display natural genetic resistance, allowing some members of the species to continue. Cleveland Metroparks, near the first U.S. entry point of beech leaf disease, is pioneering some possible treatments that may help keep individual trees alive. But communities of beech may be going the way of the American chestnut.

The decline of ash, hemlock and beech will exacerbate the climate crisis at scales both small and large. Loss of tree canopy will shrink this brook, already diminished by drought and warmer summers, depriving aquatic creatures and other wildlife of needed water. At a regional scale, loss of these species will aggravate the effects of heat and drought, and will release carbon once stored in the live trees, setting back collective efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Our best hope for these woods may be to “manage for diversity,” in the words of Aaron Bergdahl, forest pathologist with the Maine Forest Service. As trees die and new spots in the canopy open, we can plant diverse native trees — but we’ll need to water them well and help control the spread of invasive plant species like Asiatic bittersweet, Japanese barberry and buckthorn.

At what scale is such replanting possible? Watching whole forests of beech leaves shrivel and drop, I wonder.

How to take action

If you live outside the envelope already identified as afflicted with beech leaf disease and you see any symptoms, report them online to the Maine Forest Service or e-mail pictures to foresthealth@maine.gov.

Do not transport firewood.

Purchase Maine-grown plants.

Plant a diversity of native trees.

© Marina Schauffler, 2022. All Rights Reserved. Column reprints available upon request