Compound Injustice

PFAS may concentrate over time in landfills near the Penobscot Indian Reservation

A small jet boat slapped along the Penobscot River, prompting a flock of ducks to lift off from the water just below an outfall pipe of the ND Paper mill in Old Town. A team from the Penobscot Indian Nation’s Department of Natural Resources was headed out to gather water-quality data.

Having spent more than two decades monitoring pollution in the watershed, Jan Paul, the Penobscot Nation’s water resources technician, said she no longer eats duck, fish or many other traditional tribal foods. For her and for Daniel Kusnierz, the Nation’s water resources program manager, one of the hardest aspects of their work is helping tribal members navigate the risks of contaminated fish and riverine plants.

“Wild foods are important to the tribe,” Kusnierz said. “It’s who the Penobscots are.”

How much PFAS is entering the river and the full range of potential sources remain unclear due to lack of systematic water testing. But one primary contributor appears to be landfill leachate — rainwater that has collected chemicals as it percolates through layers of waste.

The ND Paper mill and several wastewater treatment plants along the Penobscot River routinely discharge a mix of wastewater and landfill leachate. “Leachate is loaded with PFAS,” said Laura Orlando, a civil engineer and adjunct professor at the Boston University School of Public Health.

“Wastewater facilities and industrial plants with conventional primary and secondary treatment are not designed to manage PFAS,” Orlando said. The first treatment plant in Maine to pilot filteration of PFAS through tertiary treatment, Anson-Madison Sanitary District, is beginning that work this month, said its superintendent, Dale Clark.

At the federal level, PFAS remain largely unregulated despite growing evidence that even minute amounts can disrupt immunological, hormonal and reproductive systems, and may increase the risk of various cancers. Last month the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed that two of the estimated 4,700 PFAS in present or past commercial use be named hazardous substances under the federal Superfund program.

As lead once contaminated fuels, paints, pipes, pencils, pottery and more, PFAS permeate industrial and consumer culture. Given their capacity to reduce surface tension, and resist oil, grease and water, the chemicals are used in papermaking, shipbuilding, textile mills, leather tanneries and semiconductor production, as well as in household furnishings, automotive products, outdoor gear, medical supplies and even personal care products.

These uses pollute wastewater with PFAS, some of which collects in the sludge generated during water treatment. In Maine, most of that sludge will now head to landfills, following a recent ban on “land-applying” sludge, a decades-old practice that has caused widespread PFAS contamination. Far into the future, landfills will likely generate PFAS pollution, even after levels of these chemicals decline in the waste stream as Maine and other states require manufacturers to phase out PFAS use in products.

That prospect of ongoing contamination could endanger members of the Penobscot Indian Nation. Since Maine enacted a ban on commercial landfills in 1989, the state has acquired and licensed three landfills, all along a 50-mile stretch of land at the heart of the Penobscot Reservation.

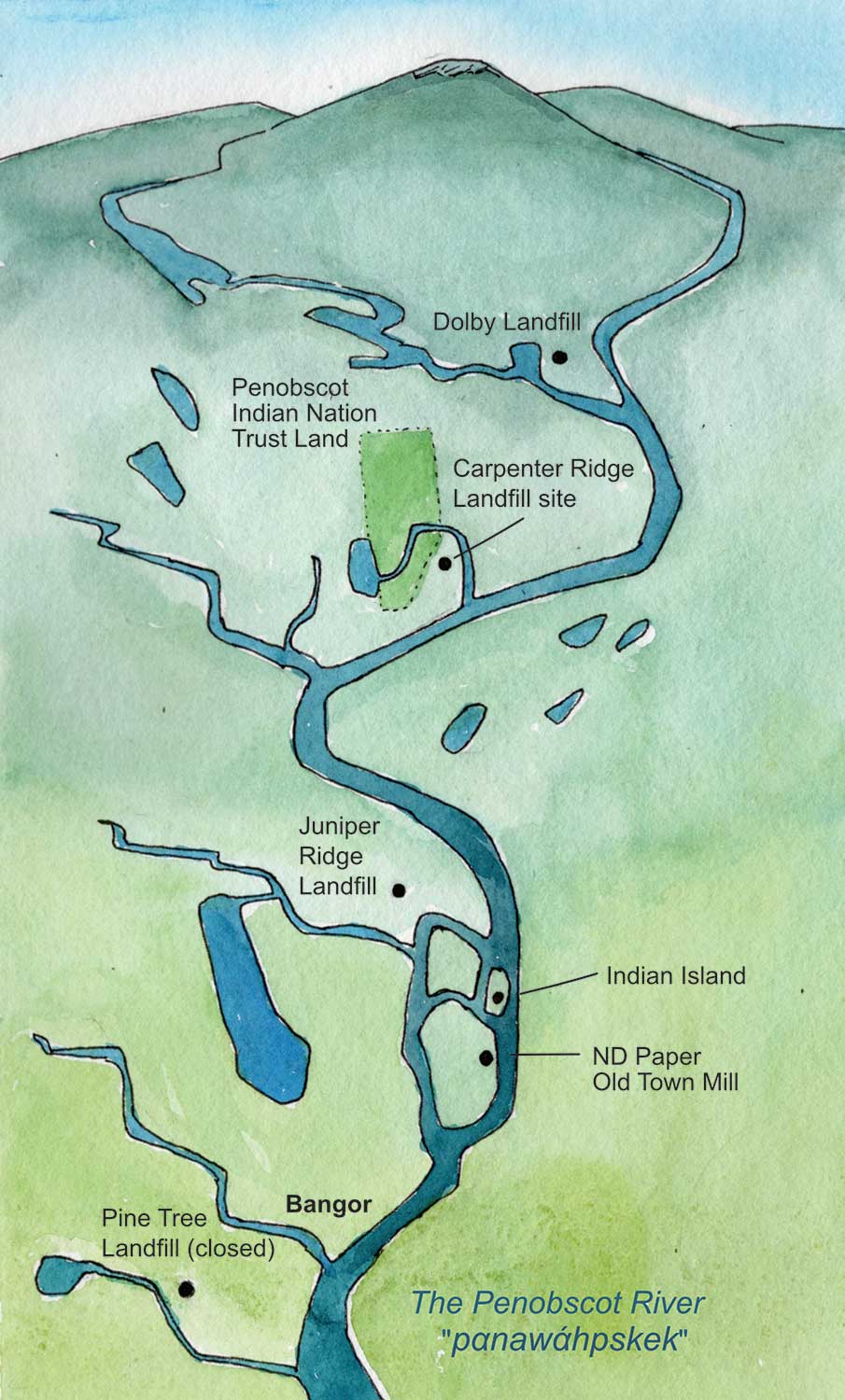

The Penobscot Indian Reservation encompasses the Penobscot River and 200 islands within it, including Indian Island. Three state-owned landfills and a closed private landfill are located in the watershed surrounding the Reservation. Illustration by MollyMaps.

A river rimmed by landfills

Juniper Ridge is the largest state landfill, a 200-foot-high waste plateau perched five miles northwest of the Penobscot Nation’s home at Indian Island. Since the state acquired the landfill in 2004, it has been run by a Vermont-based firm, Casella Waste Systems, Inc.

PFAS levels in leachate are a direct reflection of the waste a landfill receives, said Samuel Nicolai, Casella’s vice president of engineering and compliance. A 2019 study Casella commissioned at its Vermont landfill, assessing waste materials expected to have some PFAS, found the compounds in 95 percent of the samples – particularly carpets, mattresses, furnishings and textiles. PFAS also enters landfills in construction debris, household waste and sludge.

Leachate at Juniper Ridge is collected through a system of pipes and pumped to a million-gallon storage tank on site. Each weekday, about five truckloads of the leachate are transported from the tank to the ND Paper mill, said Jeffrey Pelletier, an engineer with Casella, who estimates the total annual transport at 16 million gallons.

The plastic-lined cells of the Juniper Ridge Landfill are designed to collect leachate that is pumped to a million-gallon storage tank before transport to the ND Paper mill along the Penobscot River. Photo by Marina Schauffler.

There the leachate mixes with mill effluent and undergoes secondary treatment before discharge into the Penobscot River, according to a 2019 permit issued by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. At the mill, said Jeff McBurnie, director of compliance with Casella, there is “nothing that would qualify as treatment for PFAS.”

“We’re (all) trying to treat a problem we don’t have the guardrails for,” McBurnie added. “We haven’t been given the ability to manage (PFAS) because we didn’t know about them, and we can’t identify the scope of the problem because these materials are proprietary. Do I want to vilify a whole class of materials? I wouldn’t have to if some manufacturers were more forthcoming.”

(The Maine Monitor sought to visit the mill’s wastewater treatment facility and interview staff, but repeated calls and emails spanning several weeks to Scott Reed, ND Paper’s environmental and governmental affairs director, and Brian Boland, the company’s director of communications, went unreturned.)

In recent state-mandated PFAS testing of landfill leachate, Juniper Ridge Landfill reported high levels of several PFAS compounds, and a second state-owned waste facility in East Millinocket, Dolby Landfill, had the second-highest reading for PFOA (at 3,080 nanograms per liter), a commonly found PFAS, among the 41 landfills reporting. A closed private landfill in Hampden owned by Casella was among the top 10 for the highest combined level of the six PFAS measured. Its leachate goes to the Bangor wastewater treatment plant where it receives biological treatments before discharge into the river, said Amanda Smith, the city’s director of water quality management.

The leachate captured at Dolby is pumped to East Millinocket’s wastewater treatment facility, then discharged into the Penobscot River’s West Branch, said Blaine McLaughlin, the town’s water works utility superintendent.

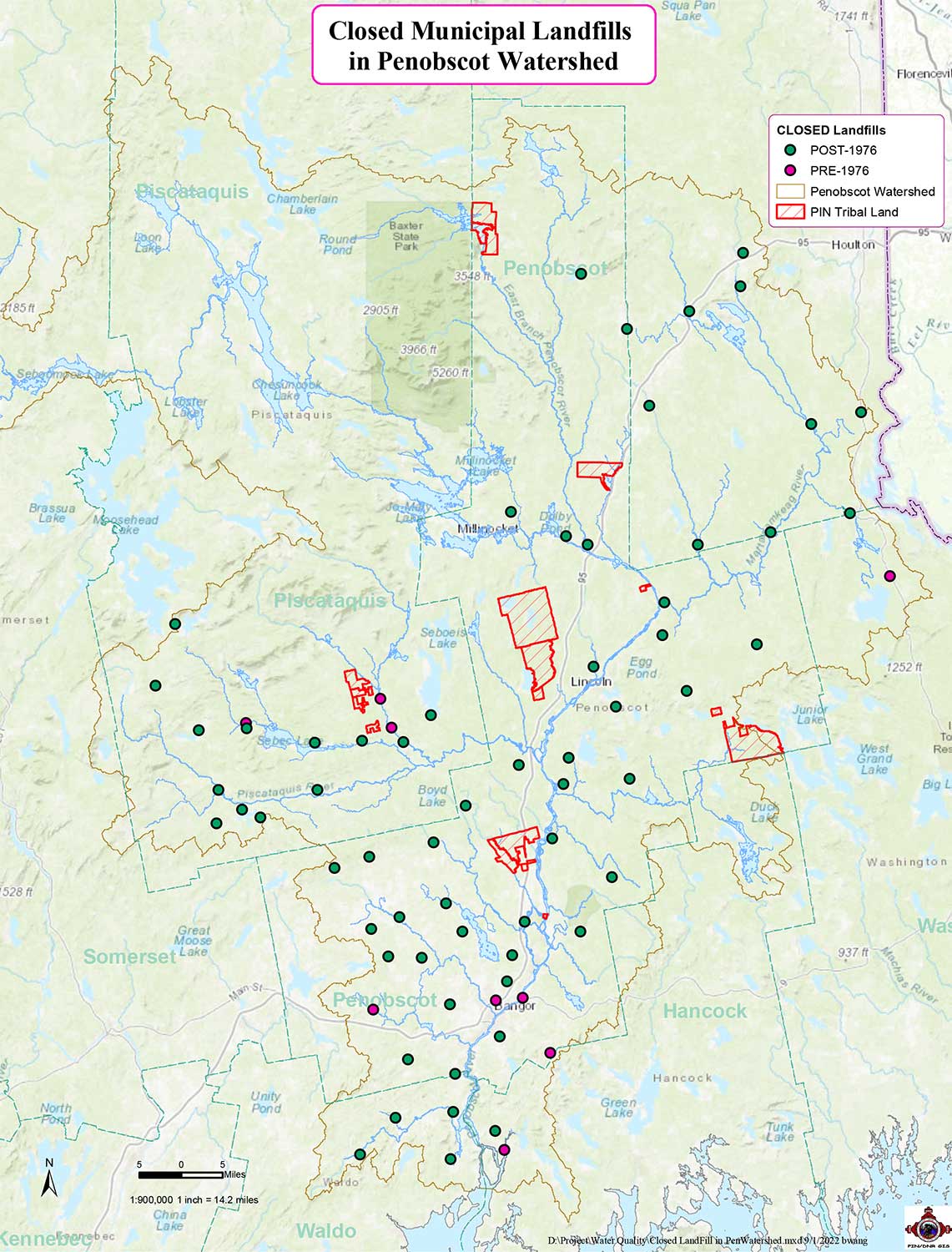

There are more than 400 closed municipal landfills around Maine, 72 of them located in the Penobscot River watershed. Older unlined dumps can release contaminants like PFAS into groundwater or surface waterways. This Penobscot Indian Nation map shows the dump sites in relation to the Tribe’s Trust Lands, often used for hunting and fishing. Map prepared by Binke Wang, Penobscot Nation GIS Specialist, with landfill data from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection.

The Maine DEP has identified 72 closed landfills in the Penobscot River watershed as well (see map), many of them unlined old municipal dumps that could leak chemicals into tributaries. For example, the agency found PFAS when sampling monitoring wells in 2020 at Old Town’s closed municipal landfill near Pushaw Stream, according to David Madore, the DEP’s spokesperson.

Kusnierz is concerned about PFAS contaminants emanating from Dolby Landfill and other sites within the watershed. “We’re in the process of trying to identify all the different potential sources,” he said, including all the “old, unregulated places.”

Paper Mills and PFAS Waste

Paper mills can be major contributors to PFAS contamination, evidenced by leachate and sludge levels, but the industry is notoriously reticent about sharing information. A recent leachate sampling mandated by the state at 41 mill landfills found high readings; the highest ones reported, according to data posted online by the Maine DEP, were at the Twin Rivers Mill in Madawaska, which produces food packaging specialty papers. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection has found numerous contaminated wells in Fairfield, Oakland, Benton and Unity associated with sludge spread from the Kennebec Sanitary Waste District, whose largest contributor is the Huhtamaki mill in Waterville (producing Chinet plates and molded fiber trays).

The most intensive PFAS use in paper production is associated with food packaging products designed to be water- or grease-resistant. PFAS tends to be used for papers and boards that need to withstand “aggressive conditions,” said Lokendra Pal, a forest biomaterials researcher at North Carolina State University. Where PFAS is used in moisture-barrier and “release” papers, it is likely applied through a surface coating or by submersion in baths. PFAS in food packaging papers came into use in the 1970s and 80s, largely replacing parchment paper and waxes.

Most other coated printed and packaging papers tend to rely on clay-based coatings rather than PFAS, said graphic arts consultant Karl Schoettle, who has worked for decades with paper suppliers. PFAS coatings are less likely in mills producing uncoated papers, paperboard or containerboard, he said, but the chemicals might still be used in some manufacturing equipment, such as helping pulp to pull off rollers.

PFAS are used in some printing inks and can surface in recycled paper products (due to contaminated food papers in the recycling stream), wrote Håkon Austad Langberg, senior engineer at the Norwegian Technical Institute.

Reconstructing production methods at Maine’s 35 historic paper mills would be “nearly a Herculean task,” given the numerous changes in ownership and production types over the decades, said forestry expert Lloyd Irland. Some clues to former production may come from the PFAS chemicals themselves because each compound has a distinct chemical signature that can be traced to certain manufacturing processes. This sub-field of environmental forensics is likely to expand as the breadth of PFAS contamination becomes evident.

A restoration effort thwarted

When PFAS surfaced as a concern, the Tribe and a diverse group of collaborators had recently completed a decades-long effort to remove two dams from the Penobscot River, allowing the return upstream of sea-run fish. It was a major step toward restoring the health of the river ecosystem, which Kusnierz said is the “lifeblood of the Penobscot Nation.”

As large numbers of sea-run fish began returning to the river, the Tribe wanted to know whether they were safe to eat. In response, federal agencies undertook a study of contaminant levels in Penobscot River sea-run fish that included PFAS.

In 2021, the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry reported back that the sea-run fish contained PFAS, in addition to mercury, dioxins and PCBs. One PFAS compound, PFOS, was found in four species at levels that might cause “adverse health effects,” the report noted. “With the dams out, we were so excited for the fish to come back,” Kusnierz said, “and then we learned they have all these contaminants in them.”

A 2015 EPA study warned that a range of chemical contaminant threats was undermining sustenance fishing rights the Penobscot Nation reserved through historic treaties and the 1980 Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Act, rights reaffirmed when the tribe became a federally recognized Indian Nation that year. The report said “fish contamination prevents this right from being fully exercised, and may seriously threaten the health of community members and their traditional life ways.”

Now, Tribe members must confront the varied threats posed by PFAS, a vast class of chemicals in global use that remains largely untested. “The sea-run fish are more toxic than the river-run ones,” said Paul, the Nation’s water resources technician. “It’s crazy to think it’s just the river that’s polluted. The ocean is getting it from everywhere.”

The extent of PFAS pollution in Penobscot River water and in the broader watershed ecosystem remains unclear due to lack of systematic testing. To date, there are only a few isolated data points: For example, in 2020, biologists with the Maine DEP found relatively low levels of one PFAS compound, PFOS, in Penobscot River fish, and this summer the Shaw Institute (a scientific research organization in Blue Hill) found low concentrations of another PFAS compound, PFOA, in three of the four samples taken in the vicinity of Old Town. In response to questions about food web impacts, the Maine Department of Inland and Wildlife wrote that “there is insufficient data” for understanding how PFAS migrate into wildlife and affect the food web.

The idea seems to be that “’It’s OK to pollute just a little bit,’” Paul added, “but a little bit accumulates over time.”

In the case of PFAS, accumulations spanning more than 50 years could keep cycling through rainwater, soils, rivers, lakes, groundwater, bays and oceans for centuries.

‘It’s our responsibility’

The enduring toxicity of PFAS compounds represents a threat, not just to the health of tribal members but to traditions that have bound them through millennia to the waterway they know as “pαnawάhpskek.” The river is central to their fishing, hunting and gathering traditions, to their spiritual practices and to their creation stories.

“Our holy place is not in the Middle East but right here in our watershed,” said Darren Ranco, a member of the Penobscot Nation and a professor of anthropology at the University of Maine. “The river is a relation that is in many ways sacred; it’s not an ‘other,’ a resource. We will take care of it to the extent we can. It’s not about ownership; it’s our responsibility.”

That ancestral responsibility, carried down for more than 10,000 years, has manifested in the last 25 years in a tribal commitment to test waters at roughly 90 sites throughout the Penobscot River watershed and advocate for policies supporting the river.

For more than two decades, Daniel Kusnierz and Jan Paul have worked for the Penobscot Indian Nation’s Department of Natural Resources, running a water-quality testing program that samples at roughly 90 locations throughout the watershed. cr: Marina Schauffler

Toxic pollution is “another legacy of harm from colonization,” Ranco said, with the potential risk of PFAS “particularly damaging because it is so difficult to address.” Colonization left Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Micmac and Maliseet tribes with a tiny fraction of the territory Wabanaki people once occupied in the Northeast. A quarter of Maine falls within the Penobscot River watershed, but only the river and 200 islands remain in the Penobscot’s tribal care.

In 2012, the Maine Attorney General’s Office asserted that only the islands fell within the reservation, not the river, prompting a legal case that continues today. Intervenors on behalf of the state include many of the municipalities, sewer districts, paper mills and other industries that hold permits to discharge wastewater into the Penobscot River.

Following on historic land loss and the ongoing challenge to river ownership, the potential PFAS threat is “clearly unjust,” Ranco said. It can leave tribal members feeling overwhelmed by their inability to protect waters from contaminants, and sustain a livable home and traditional life ways.

“There’s a type of despair,” wrote Sherry Mitchell, a Penobscot attorney and activist in her book “Sacred Instructions,” “that is unique to those who are exiled on their own lands.”

Landfills leave a legacy

Seeking strong action on PFAS, Penobscot Nation members were encouraged by legislative action to contain chemical contamination. In the last session, that included a measure passed to end application of sludge onto farmlands and forests. With no known means to destroy PFAS, Kusnierz said, it makes sense to be “concentrating it in a more controlled environment.”

That contained setting will be Juniper Ridge Landfill for much of the PFAS-laden sludge generated statewide. The Tribe supported LD 1911, but also sought legislation to mitigate the impact additional sludge would have on the leachate load entering the Penobscot River by ensuring that leachate at state-owned landfills is treated for PFAS.

Midway between Juniper Ridge Landfill and Dolby Landfill, in a township just west of Lincoln, the state maintains an active permit on an undeveloped 1,500-acre site, Carpenter Ridge, that it calls “a potential ‘safety net’ for future landfill development.”

Juniper Ridge Landfill is expected to reach capacity in 10 to 12 years, Casella estimates. Then, “Carpenter Ridge will become the next Juniper Ridge,” Kusnierz fears, concentrating more PFAS-laden debris farther up the watershed.

The Carpenter Ridge site, less than a mile from a large tract of Penobscot Nation Trust Land that tribal members use for hunting and fishing, lies close to Mattamiscontis Stream, where the Penobscot Nation has been working to restore fisheries.

“Landfills create environmental justice issues for generations,” Ranco said. A concentration of them near the Penobscot Reservation could turn lands and waters that the Tribe views as sacred into a “sacrifice area,” he added. “Once you build it and (the contaminated waste) comes, it becomes a legacy and a permanent violation of how we’re supposed to treat the earth.”

‘Disproportionate impact’

The state acquired Juniper Ridge, Dolby and Carpenter Ridge landfills through deals made with paper mills, which were located by the Penobscot River due to the need for water in manufacturing and for wastewater discharge. As for their proximity to the Penobscot Indian Reservation, “I’m not saying it was deliberate,” Kusnierz said, “but talk about disproportionate impact.”

Working on PFAS with tribes nationwide, Kusnierz has noticed how indigenous people naturally take a more precautionary approach. “This idea of figuring out how much of a toxic chemical is acceptable is baffling,” he said. “For native people, you just don’t put things in without knowing the effects because the river is a living relative.”

In terms of any pollutant discharge, the burden of proof needs to be on chemical manufacturers to demonstrate that their products do no harm, Kusnierz added. With PFAS, “they created something before they knew how to deal with it. That feels like a really dangerous game to be playing.”

This project was produced with support from the Doris O’Donnell Innovations in Investigative Journalism Fellowship, awarded by the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University in Pittsburgh, Pa.

© Marina Schauffler, 2022. All Rights Reserved. Reprints available upon request

The State’s approach to a landfill leachate study raises questions

A legislative resolve signed by the Governor in May requires a study of leachate treatment options at two-state owned landfills — Juniper Ridge Landfill in Old Town/Alton and Dolby Landfill in East Millinocket — be completed this year. Photo by Marina Schauffler.

As the latest round of PFAS legislation took shape last winter, members of the Penobscot Indian Nation realized the proposed ban on land application of sludge and sludge-based compost, LD 1911, would redirect much of the Maine’s PFAS-contaminated sludge to the state-owned Juniper Ridge Landfill, located in Old Town near the Penobscot Reservation. The Tribe supported that legislation, said Daniel Kusnierz, water resources program manager for the Penobscot Indian Nation, but sought to ensure that landfill leachate — the rainwater that percolates through waste — is treated for PFAS before getting discharged into the Penobscot River. In response to concerns from the Penobscot Nation and the Maine-based nonprofit Defend Our Health, Rep. Stanley Paige Zeigler (D-Montville) sponsored a bill that sought to ensure PFAS treatment occurred on leachate generated at Juniper Ridge Landfill and Dolby Landfill, another state-owned facility, located in East Millinocket. Following work sessions and extensive discussions, members of the Legislature’s Environment and Natural Resources Committee voted to amend the bill to an emergency resolve, requiring the Department of Administrative and Financial Services’ Bureau of General Services (BGS) to conduct a study assessing the best means for reducing PFAS in leachate at those two landfills through treatment on- or off-site. The study, due back to the Legislature in January, must assess the feasibility, time frame and “anticipated associated costs to the state or to the operators of the landfills” of both on- and off-site leachate treatment options. Other states have undertaken similar assessments of the most promising and affordable approaches to treating leachate for PFAS. In 2019, Vermont requested that landfill owner Casella Waste Systems undertake a contracted study of leachate treatment options and costs, which was completed by a national engineering firm. The Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation then hired a different national firm to review and evaluate those recommendations. In Maine, parameters for the study process were not discussed, Zeigler said, with the Legislature “allowing the agency in good faith to put it out (to bid).” Last month, legislators were surprised to learn from The Maine Monitor that BGS received a proposal for the study from Cumberland-based Sevee & Maher Engineering nearly three weeks before Gov. Janet Mills signed LD 1875, and the firm’s discussions with the bureau had begun, according to its cover letter, two weeks before that. The proposal was subsequently converted into a contract to complete the study, the bureau confirmed. While the fiscal note for LD 1875 indicates that the bureau anticipated a cost of $50,000 to $75,000, the proposal capped a time and materials budget at $111,000. Sevee & Maher Engineering has long-standing ties with both active state-owned landfills, raising concerns among lawmakers about whether the study will be objective. It holds a contract with the state to operate, monitor and maintain Dolby Landfill, dating from 2018, and the state has paid $1.96 million, according to the bureau. At Juniper Ridge Landfill, where Casella is responsible for operational and closure/post-closure costs, Shelby Wright, Casella’s Eastern region manager of engagement, wrote that “Casella does have a current and long-standing agreement with Sevee & Maher for engineering services.” In an email response to questions, the bureau’s spokesperson wrote that it “hired Sevee & Maher Engineers to conduct the research study since they have extensive experience in landfill and wastewater operations and maintenance, and are currently under an annually renewed contract with the state providing landfill and wastewater treatment engineering for the state for Dolby Landfill operations.” The bureau did not answer whether it perceived a conflict of interest in hiring a party that has existing financial contracts at both state-owned landfills. A principal at Sevee & Maher referred questions from The Maine Monitor to the bureau. “It is important that we get a good study in order that the best process for removing PFAS from the Juniper Ridge’s leachate be used,” Zeigler wrote in an email. “If there is any impropriety in the process, we will address the issue when the study comes to us in the Legislature. The most important thing is that we get the process going to protect the Penobscot River.” Sen. Richard Bennett (R-Oxford), another committee member, expressed concern about the lack of competitive bidding and potential conflicts of interest, wanting to know “why they were qualified, how they were chosen.” The bureau’s choice of Sevee & Maher also concerned Kusnierz of the Penobscot Nation. “It doesn’t quite fit right,” he said. “I can understand you’d want to have someone familiar with the facility, but I thought it would be an independent specialist.” “In general, the consulting industry doesn’t publicize their knowledge … because they can’t bill for that time, and it doesn’t help them competitively,” said Jean MacRae, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Maine. “So as in many situations where specialized knowledge is involved, it is difficult (and more costly) to get a really independent view on the matter.”

Unanswered Questions

Casella Waste Systems, a Vermont-based firm that reported revenues of $889 million in 2021, has an operating services agreement with the state to manage Juniper Ridge Landfill. Each year, roughly 16 million gallons of leachate from that landfill go to the ND Paper mill in Old Town, according to Jeffrey Pelletier, a Casella engineer. In turn, the mill sends its wastewater treatment sludge to Juniper Ridge. As the state explores the best methods and location for treating landfill leachate, it needs complete information about how leachate is managed. Lawmakers have had no access to the “leachate disposal agreement” between Casella and ND Paper so they could not know how changes in leachate management might affect that agreement or how the agreement might influence treatment options. Casella repeatedly declined to provide a copy of its leachate disposal agreement with ND Paper to The Maine Monitor, writing that “Casella’s contractual arrangements with third parties are proprietary.” But in its operating services agreement, the state retained the right to review all Casella’s third-party contracts prior to signing. Following a month of repeated requests for a copy of that agreement to the Department of Administrative and Financial Services’ Bureau of General Services, The Maine Monitor filed a Freedom of Access Act request on Aug. 25. As of September 9, The Maine Monitor had not received the requested copy. The Maine Monitor also attempted to contact ND Paper, which operates the Old Town mill, but repeated calls and emails over three weeks to Scott Reed, ND paper’s environmental and governmental affairs director, and Brian Boland, the company’s director of communications, went unreturned.

Ten questions about PFAS answered

PFAS, a broad class of persistent synthetic chemicals, are used in manufacturing and are present in many consumer products, particularly those designed to resist oil, heat and water (like the rain jacket shown). Widespread PFAS use creates many pathways of potential contamination. Photo by Marina Schauffler.

Why is exposure to PFAS a concern?

Toxicological research shows that per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) can disrupt hormonal, immune and reproductive systems, and can increase the risk of various cancers. In June, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) dropped its drinking water “health advisory level” for two of the most common PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, to close to zero, levels too minute for current technology to detect. Yet some exposure to these chemicals is virtually inescapable now; a federal CDC report found 97 percent of blood samples taken from Americans contained PFAS.

What are PFAS chemicals in?

One needn’t look far to find materials containing PFAS. They’re in construction products (such as paints and sealants), electrical equipment (like coated wires), printing and photographic materials, metal coatings, firefighting foam, ammunition, boatbuilding and automotive products, pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, ski wax, artificial turf and countless household products — cleaners, adhesives, polishes, pesticides, food storage (such as takeout containers and fast-food wrappings), nonstick cookware, outdoor gear, electronics, stain- or water-resistant furnishings (like couches, mattresses and carpeting) and even some clothing and personal care products, Maine is among the first states to start mandating disclosure of PFAS in products, slated to take effect in January (unless an effort by trade groups to delay the measure succeeds).

How are PFAS chemicals getting into waters?

Commercial and residential uses of PFAS contribute some chemicals to wastewater, but a larger portion likely comes through manufacturing. In Maine, PFAS are or have been used in industrial production of grease- and water-resistant paper and paperboard, leather products, shoes, textiles and semiconductors. Historic use of fire-fighting foam (specifically designed for combustible liquids) has also led to groundwater and surface water contamination. PFAS are now so ubiquitous in the water cycle that they are falling in rain.

Why are they called “forever chemicals”?

PFAS persist indefinitely in natural systems and accumulate within bodies for years. “Persistence is the key factor that lets pollution problems spiral out of control …,” wrote a team of international scientists. “(It) enables chemicals to spread out over large distances, causes long-term, even lifelong exposure, and leads to higher and higher levels in the environment as long as emissions continue.” While other pollutants — such as dioxins and PCBs — are also persistent, there are far fewer of those compounds. PFAS, synthetically manufactured chemicals with extremely strong carbon-fluorine bonds, number at least 12,000. Most research has focused on fewer than 100 PFAS compounds, and even in this small subset, the ecological impacts, physiological effects and potential health concerns differ markedly.

Why are PFAS so prevalent in Maine and not elsewhere?

Water activist Erin Brockovich reports that Maine has some of the highest levels of PFAS water contamination she has seen in her work with communities around the country, possibly because this state is at the forefront of testing. PFAS are in global use and still actively produced, so no region will likely escape the ecological, economic and public health challenges. In the words of Jean MacRae, a University of Maine professor of civil and environmental engineering, “The more we look, the fewer places we’ll find without contamination.”

Is the full extent of the contamination known?

While states like Maine are actively testing to determine the extent of contamination, the scope of the testing is no match for the estimated 4,700 PFAS compounds in present or past commercial use. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection assesses water samples for 28 PFAS compounds, but its interim drinking water standard only covers six. Sampling protocols for commercial labs typically include 18 to 24 PFAS, said Linda Lee, a Purdue University environmental chemist, while research labs may sample up to 70 compounds. “Fifty to 70 percent of what I’m finding (in samples at Purdue’s lab) aren’t being tested by the commercial labs,” she said. She’s convinced that the PFAS evident in standard water testing are a small subset of what may be in soils or wastewater sludge. The sludge, she said, “could potentially have hundreds (of PFAS compounds).”

What’s Maine doing to address this crisis?

The short answer is a lot. The state government has moved with uncharacteristic speed to address PFAS contamination through many measures, including the world’s first staged ban on use of PFAS in most products (taking full effect in 2030), and a ban on the land application of sludge and sludge-based compost. State agencies are openly sharing data gathered on PFAS. Testing, research and policy demands have diverted untold hours and resources from agencies that would otherwise be directing them toward other important challenges.

Did the manufacturers of these chemicals know they were problematic?

PFAS were first manufactured primarily by 3M and DuPont, chemical corporations known for PFAS coatings like Scotchgard and Teflon. They knew by the 1960s from their own lab tests that these enduring chemicals posed serious health risks, but continued to produce and market the “legacy” or long-chain PFAS (those with more carbon molecules). The corporations finally phased out two of the most common compounds: PFOA and PFOS, but in their place introduced short-chain replacements (what they termed “GenX” PFAS), with fewer carbon molecules, that were marketed as safer. Growing evidence indicates that these short-chain compounds are just as toxic, and more mobile and persistent in ecosystems.

Why aren’t these products regulated to protect public health?

The EPA knew about the dangers of PFAS compounds by 2001, due to a 972-page public brief shared by attorney Robert Bilott, whose story of battling DuPont to get that voluminous evidence is documented in the film, “Dark Waters,” and his book, “Exposure.” The agency failed to take substantive action until recently. Last month, the EPA recommended PFOA and PFOS, two common PFAS chemicals manufactured for decades, for inclusion as hazardous substances under the federal Superfund program, but the agency has taken no action to phase out or ban production of PFAS.

Is it possible to destroy these chemicals?

Any lasting solution to PFAS contamination depends on developing technology to destroy the chemicals, rendering them into harmless elements. Scientists are testing all sorts of techniques such as supercritical water oxidation, thermal regeneration, electrochemical degradation, ultrasonication, pyrolysis and ultraviolet-initiated degradation, but nothing has progressed beyond lab experimentation. Some methods are highly energy-intensive, and none could recapture all the PFAS now cycling through water systems, the atmosphere and soil ecosystems. There is no simple fix on the horizon.