More Consensus than Controversy

In her Supreme Court confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Justice Amy Coney Barrett sidestepped questions about climate change, saying it was a “very contentious matter of public debate.” As a matter of fact, it is not.

An overwhelming scientific consensus recognizes human-caused climate change, and two-thirds of Americans want the government to address it. How governments go about tackling this existential threat may provoke controversy, but the stark-as-wildfires reality of climate upheaval is not up for debate.

Recent surveys and polls conducted in Maine demonstrate far more consensus than controversy around climate realities and the urgent need to confront them.

‘Accelerating’ awareness

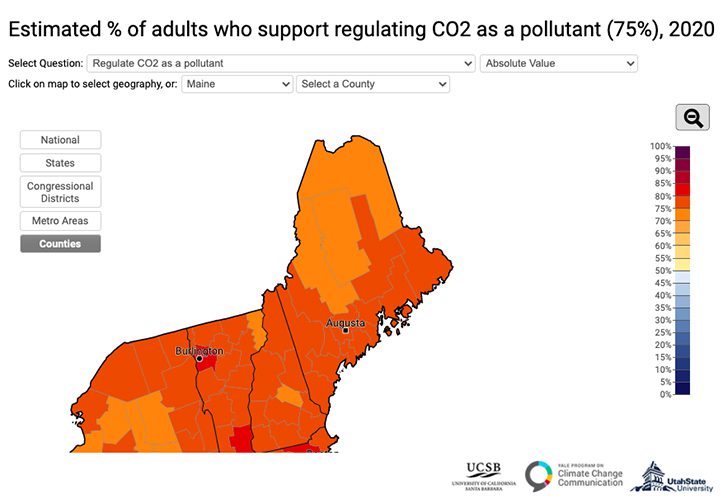

Each September, researchers at the Yale Program on Climate Communications release updated “climate opinion maps” for the U.S. by county and congressional district. The trope of “two Maines” doesn’t hold up in its 2020 poll, which shows a strong congruence in climate views between residents of Maine’s southernmost 1st District and its largely rural 2nd District.

Across Maine, roughly three-fourths of adults support regulating carbon dioxide as a pollutant. People in Maine’s northwestern counties are slightly less supportive than residents in the rest of the state, but that translates to a mere 3 percentage point difference between Maine’s 1st and 2nd Congressional Districts. Courtesy of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Respondents from each district, answering 30 questions on global warming beliefs, risk perceptions and potential policy actions, came out – on average – less than 5 percentage points apart. Some policies, like providing tax rebates for solar panels and electric vehicles, garnered strong support, ranging from 81 to 86 percent, in each Maine county.

That common ground was evident in the inclusive and transparent process that marked the Maine Climate Council’s year-long effort to draft a Climate Action Plan, said Rep. Lydia Blume (D-York Beach), who serves on the Council. A legislator since 2014, she has witnessed “a sea change of attitude,” with public awareness of climate “really accelerating” as people began to experience first-hand “how scary and how real it was.”

Through intensive months spent drafting and refining climate strategies for the Plan, Blume was impressed by “how involved and engaged” participants were. More than 200 citizens and organizational representatives in six ongoing working groups developed strategies, incorporating findings of a 370-page “Scientific Assessment of Climate Change and Its Effects in Maine” co-authored by 37 scientists.

“It took a lot of synergy to make this happen,” Blume said, crediting the staff of the Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future (GOPIF) who worked to keep the process open – welcoming the public at all Council and working group meetings, and sharing online meeting videos and notes.

Public perceptions of risk and harm

To gather public input, the Maine Climate Council circulated surveys and received more than 4,400 responses, representing 74 percent of Maine’s zip codes. Designed for feedback on climate strategies, not as a polling instrument, the surveys were still “instructive about the risks foremost on certain respondents’ minds,” said Anthony Ronzio, GOPIF’s deputy director.

Thirty-seven scientists co-authored the 370-page “Scientific Assessment of Climate Change and Its Effects in Maine.” The Maine Climate Council and citizens referenced its findings while drafting strategies for the state’s Climate Action Plan. Illustration by Jill Pelto.

A warmer ocean, extreme weather events, sea-level rise and drought topped the list of climate change risks that survey respondents saw as endangering their communities. Top concerns for “aspects of your community” that would be harmed included people’s health, wetlands/coastlines/intertidal settings, wildlife and Maine’s economy (particularly agriculture and fishing).

Alongside the surveys, Council staff held numerous meetings, but outreach “would have been really different had we not had the pandemic,” said Ania Wright, the Council’s youth representative, noting that events like a planned day-long student forum had to be canceled.

Coronavirus, which might have derailed the Council’s work, instead reinforced the recognition that climate change poses another potentially devastating health and economic crisis. “COVID has shown us the need” for strategic action, said Blume, while helping to illuminate some shared solutions – like increased access to broadband.

Maine’s renewed commitment to climate action – even in a pandemic – mirrors findings of a recent national survey done by Stanford and the nonprofit Resources for the Future: Despite COVID-19 fears and associated economic losses, “more Americans than ever before consider the (climate) issue to be extremely important to them personally.” Researchers concluded that “concern about the environment seems not to be a luxury good.”

‘A sense of urgency’

Young people feel a particular sense of urgency on climate action, Wright said, and “want (the Plan) to be bolder and centered in climate justice.”

The number of people nationally who see climate change as a significant personal concern is growing, but in Yale’s survey a large gap remains between Maine residents who recognize “global warming will hurt plants and animals” (68 percent) and “harm future generations” (69 percent), and those convinced it will harm them personally (38 percent).

A growing number of Mainers do feel direct impacts of climate change as communities contend with record-breaking drought, the eastward migration of lobsters, and the erosion of ski seasons and maple sugaring. Vulnerability mapping done for the Climate Action Plan reveals just how much of Maine could be hard-hit by different impacts in the future.

Blume sees signs of “a bipartisan realization” in which climate change is “more accepted as a reality.” Addressing the challenge will be hard when budgets at every level are strained, but economic analyses commissioned by the Maine Climate Council reflect the even higher cost of doing nothing. “The Plan has laid out what we could lose if we don’t act,” Blume said.

That action could begin in the next legislative session, and Maine residents should discuss climate concerns with their representatives, who will receive the final Climate Action Plan next month.

“The need for public input and action is not over,” Wright said. “This is more marathon than sprint.”

© Marina Schauffler, 2020. All Rights Reserved. Column reprints available upon request