Construction is booming where wildfires leveled homes in California and hurricanes left rubble in Florida — even as major insurance companies stop writing new policies in these states, deterred by the growing likelihood of climate-driven disasters.

Maine is not at imminent risk of having insurance companies withdraw, but as cascading catastrophes destabilize the industry, we are vulnerable.

Our state might be just one disaster away from significant disruptions in its insurance marketplace, in the estimation of Charles Colgan, a former Maine state economist who directs research at the Center for the Blue Economy in Monterey, California.

Maine should do more to prepare for ripple effects from disasters elsewhere and for extreme weather events here. Climate strikes are capricious, and insufficient insurance planning could prove costly, Colgan added: “The risk is real; it’s rising all the time. It’s not an immediate problem — until it is.”

Warning signals

Colgan made that observation just days before flash flooding struck Vermont, which — like Maine — has long been viewed as a “climate haven” less vulnerable to extreme weather. Destruction from the deluge rivaled the impact of Tropical Storm Irene, in which Vermont’s damages totaled nearly $750 million.

The 2011 storm prompted Vermont to increase its resilience and to anticipate how climate risks might reshape its insurance industry. In 2021, the state’s Department of Financial Regulation issued a report with recommended changes, a model that Maine and other states could consider.

For decades, the insurance industry moderated risks by diversifying. But climate risk is best described by the movie title, “Everywhere, Everything. All the Time.” Benjamin Keys, a professor of finance at University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, told Congress in March.

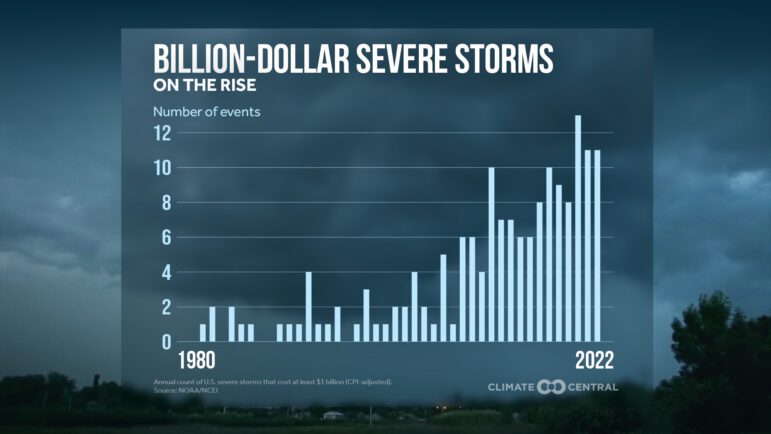

In recent years, the United States has experienced roughly 20 disasters a year with damages topping $1 billion, a sixfold increase from the 1980s.

Compounding risks raise the costs to insurance companies of insuring their own businesses (known as “reinsurance”). “Reinsurers know far more than the government in terms of [climate] risks,” Colgan noted, “but researchers cannot access their data since it is the basis for their business.” The world’s largest reinsurer, SwissRE, anticipates that property losses due to climate-driven natural disasters could increase 60 percent by 2040. Not surprisingly, reinsurers’ rates are rising.

Those escalating costs for insurance companies, coupled with proliferating claims, translate to higher premiums and less coverage for property owners.

According to the Insurance Information Institute, the national average cost of homeowner premiums rose 40 percent between 2010 and 2019. This year in Florida, the average annual premium is expected to hit $6,000. Meanwhile, the institute reports, home replacement costs nationally have risen more than 55 percent since 2019.

High-risk areas like Florida have seen some insurance firms go out of business, forcing more residents to enroll in a state pooled-insurance program (sometimes known as a FAIR plan). In Florida, that plan is now the state’s largest insurer with 1.2 million customers. Oversubscribed state programs may operate with deficits and have inadequate reinsurance, potentially undercutting their capacity to cover claims.

Maine has no FAIR plan, but it does have the statutory means to create one should a particular type of insurance become “unavailable or unaffordable,” according to a spokesperson for the Maine Bureau of Insurance.

She noted that the state’s Property Insurance Cancellation Control Act “does allow insurers to non-renew all of their policies at once if they decide to withdraw from the market in Maine, but only after the Bureau approves a withdrawal plan that proves the availability of substitute coverage.”

Those restrictions don’t apply, though, to insurers that stop writing new policies.

Assessing insurance risks in Maine

A recent federal report by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office, prepared in response to an executive order on climate-related financial risk, concluded that states’ efforts to address climate risk impacts on the insurance industry are “preliminary” and “fragmented.”

It issued 20 recommendations for state insurance regulators, but it’s not yet clear which ones Maine might implement.

The Maine Bureau of Insurance spokesperson wrote that the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ (NAIC) is reviewing those recommendations and “Maine plans to work in a coordinated fashion with other NAIC member jurisdictions in taking appropriate actions in response to the report.”

Maine’s Insurance Bureau is active in NAIC’s Climate and Resiliency (Executive Committee) Task Force, and in 2021 it joined the NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Survey, which 27 states use annually to gather non-confidential information from insurance companies about their assessment and management of climate-related risks.

The Governor’s Office of Policy Innovation and the Future, which coordinates Maine’s climate planning process, indicated that “our office has not conducted any specific analysis on insurance markets/climate implications, but we expect this need to be a topic when the Council restarts work in September.” That discussion may happen under the auspices of a new “Community Resilience Working Group” being named this summer.

Maine should prepare for the possibility that private property and casualty insurers stop offering coverage here, Colgan said, by creating a plan that could potentially incorporate a risk assessment, recommendations for creating a pooled risk fund/FAIR plan, and means to reduce risk so that insurance companies are less likely to withdraw.

The plan might also outline ways for insurers to help further Maine’s climate goals—providing incentives for measures that simultaneously reduce risk, control costs, lower emissions and foster greater resilience. For example, insurance incentives to replace single-pane windows with double-pane ones would lower wildfire and storm risk while cutting fossil fuel consumption.

Vermont’s plan cites insurers that provide higher replacement values for “green building” materials. Research by the National Institute of Building Sciences found that every dollar invested in protecting assets from natural disaster damage could result in up to $13 in savings.

Climate and economic risks

Flooding represents Maine’s largest financial risk, according to its 2020 Climate Action Plan. That risk has been on display this summer, with inland flash floods causing significant damage in settings like Lewiston-Auburn and Jay, where the town’s estimates for road damage alone total nearly $4 million.

The nonprofit First Street Foundation, which analyzes property risk factors, estimates that 26,000 Maine properties outside the federally designated flood zone could flood over the next 30 years. Wind damage (not covered by federal flood insurance) could be substantial as well, given Maine’s older housing stock.

As the nation’s most forested state, “Maine is woefully underestimating fire risk,” Colgan observed.

Even before global warming intensified drought cycles, Maine experienced over three months without precipitation in 1947, followed by a series of wind-driven conflagrations that scorched 220,000 acres and destroyed more than 1,000 homes between Western Maine and Jonesboro, including much of Bar Harbor.

Risks from these threats can be reduced by preventive measures — such as retreating from flood-prone zones, building more storm-resilient structures, and creating ‘defensible space’ from wildfires.

A stronger statewide building code would be a logical place to start, but Colgan said that’s been discussed for decades without ever being approved by the Legislature.

“I hold no hope that we would put it in place before a disaster,” he said, “but afterward we might.”

‘Overexposed’

As more states step in to become an insurer of last resort, the nation could inadvertently exacerbate a growing “climate bubble” of overvalued properties that don’t account for climate risks.

“People can deny climate change because it’s all far away, elsewhere, in the future,” Colgan said. “But when the insurance company cancels your policy and you can’t sell your house, that’s when things get real.” If properties become unsaleable because they’re no longer insurable, the housing market could collapse and loans could go unpaid. “Now you have 2008 [the Great Recession] on steroids,” he added.

Colgan is not alone in that assessment. The president of a leading insurance firm, Aon PLC’s Eric Andersen, told the Senate Budget Committee in March, “Just as the U.S. economy was overexposed to mortgage risk in 2008, the economy today is over exposed to climate risk.”

Managed well, insurance can help promote resilience and sound risk management while providing a critical safety net. Without sufficient planning, though, it can widen a growing gap between those who can afford insurance and those who lack adequate coverage and receive no help to start anew following catastrophes.

Maine may need to rethink the nature of insurance in this unpredictable age, going beyond the parameters of conventional profit-driven models. Collaboration with states confronting similar challenges could help.

Those conversations should start soon, in advance of a disaster — not in its aftermath.